Stop using your health wearables

Against the tyranny of data

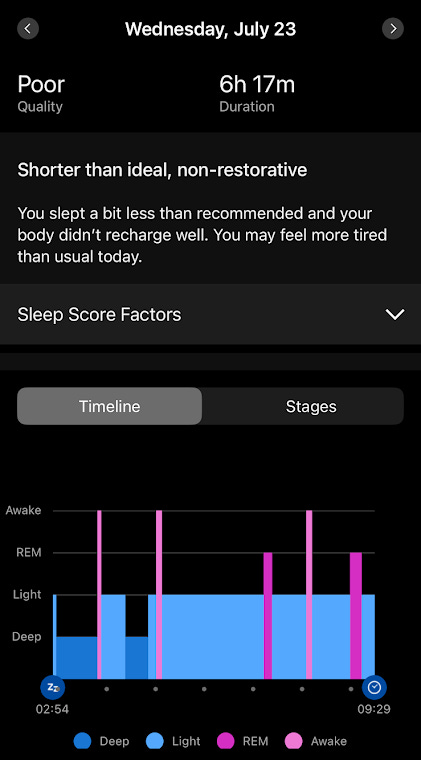

I’ve slept with my watch on almost every night for almost five years. I got a smart watch to track runs (and skis, and bikes, etc.) and I figured, hey, I have it, so I might as well use it to its full potential. Now that I’ve got thousands of days of data, what conclusions can I draw about my health? After looking at the data, I can say with high confidence the following things are true:

1a) Putting any chemicals (caffeine, nicotine, other drugs) in my brain is not good for sleep quality. 1b) Drinking is particularly bad for sleep.

2) Vigorous exercise before sleep harms my sleep quality.

3) I feel my best when I sleep for 8-9 hours.

Collecting this data feels useful. But can I actually use it to improve anything about my health? Is any of this actionable? An honest reckoning points to “no.” Unfortunately, more data is not more information. I already knew these so-called insights before collecting all of that data. And so do you.

“Wearables” have proliferated like kudzu across the health and wellness landscape. Smartwatches, wristbands, armbands, and rings track various biometrics, notably heart rate, sleep duration and quality, stress levels, blood oxygen levels, and body temperature—even, I’m told, menstrual cycle tracking. But, I wonder, to what end?

I am not picking a fight with activity tracking apps (i.e. Strava), though some day I probably will.1 Instead, I am motivated by a concern that health wearables represent misplaced effort and may even actively harm users.

My Primary Concerns: Devaluing embodied knowledge and exacerbating health anxiety

A common business-school adage says “you can’t improve what you don’t measure.” I’ll go on the record as saying this is another shortcoming of management-consulting brain; there are plenty of complex systems that you can improve without direct measurement, and your body is one of them.

In a hyperscientific convenience poll I’ve been conducting in group messages, at work, in the sauna, and at trailheads, I’ve investigated why and how people in their 20s-40s buy and use wearables. You’ll note that my sample skews young, healthy, and outdoorsy, which is also where my conclusions will be most valid (because that describes me).

By far the most commonly-cited reason for seeking out wearables has been SLEEP. People are, understandably, concerned about their time spent horizontal. I’ve written about my own prioritization (or lack thereof) of sleep multiple times and it was my own driving motivation to wear a smartwatch nonstop for years. The second most common item of concern was heart rate. Relatedly, some of the mountain athletes with whom I’ve spoken highlighted the training and recovery-related metrics these devices provide. HRV (heart-rate variability) tracking, training load management, and readiness scores all fall into this category. Though it came up in my sampling, I will be excluding from this discussion menstrual cycle tracking as I, unsurprisingly, have no perspective to contribute on this point beyond “this seems useful” (though I don’t know the alternatives).

In each of the use cases mentioned above, there are insights you can glean from these measurements. I don’t deny that. What I do deny is that these insights are marginal in a meaningful sense, beyond what you already know based on basic scientific knowledge and signals from your own body.

When I drink five beers or go to sleep at 3am, I don’t need a machine learning algorithm synthesizing insights from “50+ health and wellness metrics” to guess that I’m going to have shitty sleep (in fact, just one beer will do it). Nor do I need a Readiness Score or Training Status to tell me when I’m strained and need to rest; every time my watch has ever flashed one of these notifications, my body had already made it clear that I was pushing it too hard by being sore, exhausted, or hinting toward sickness. As I mentioned in the opening, we all already know how to sleep well. Our bodies are giving us plenty of signal to work with regarding recovery, when we’re getting sick, and what feels good or bad. We just need to listen and act on it.

Furthermore, this level of optimization is misplaced effort unless you’re already at the frontier of health interventions, which most people, Bryan Johnson notwithstanding, are not. Worrying about your average resting heart rate or changes to your HRV are the law of triviality incarnate: users giving disproportionate weight to trivial issues. Michael Pollan said about diets: “eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” Most athletes should take a Pollanian approach to health, too: exercise, not too much. Sleep plenty.

In summary, these devices pathologize health anxiety. In fact, the inspiration for this polemic stemmed from visiting a friend who has a history of diagnosed health-related anxiety. The guy is in his late twenties, in fantastic physical shape, and eats well: in short, he’s healthy. Shortly before my visit, though, he discovered a small bump in his leg and has gone to a few doctors about it. He admitted that his Oura ring was reporting higher indicators of stress and heart rate in line with his concerns over the leg lump. As he was describing these stats, I could actually see his heart rate increasing in real time. There was a negative feedback loop going on here: observing his stress levels increasing was increasing his stress levels further.2

Upon reflection, I realized I was doing the same thing with sleep. The very act of measuring sleep led to an observer effect, whereby knowing I’d be registering a bad score would cause additional stress, which would worsen the score, etc. etc.. Sometimes when I’d wake up feeling refreshed, I’d look at my watch and see a bad score relative to how I felt, and then actually begin to feel worse. The measurements were creating a self-fulfilling prophecy!

One friend in the sauna almost convinced me that the gamification of some wearables (e.g. the WHOOP data streak) can incentivize healthier behaviors. But in reality, this kind of structure is Goodhart’s Lawing you into optimizing for device usage (to the benefit of the tech company) rather than optimizing for health outcomes. If all of the concerns above (and in the appendix) are valid, then increased use of the device does not mean you’ll be healthier. If using the devices does create net stress, then using it more will only worsen outcomes.

In short, I’ve started taking off my watch at night and am ignoring my insurance company’s offers of free and discounted rings, watches, and bands. Until the tech advances enough to where my watch can sing me lullabies to make me snooze faster and sleep deeper, I’ll be doing things the old-fashioned way: when someone asks me “how’d you sleep?” I’ll answer frankly, based on how I feel, without glancing down at my watch screen.

Appendix: Other, less interesting concerns with wearables

Do wearables work?

Frankly, I’m punting on this one. Different wearables use different measurement techniques, and folks I’ve talked to that have multiple wearables (e.g. a Garmin smart watch AND an Oura ring) report different results between the two. There may be external validity issues with comparing across wearables, but for now let’s grant that the measurements are at least somewhat accurate.

Who wants you to use them?

Though I’ve all but given up on efforts against the technology panopticon that now defines our lives (2012-Michael would be ashamed), it’s still worth asking: cui bono? There is a lot of money to be made in pathologizing your health anxiety. The “consumer wearables” sector is broad, and it’s hard for me to disaggregate things like glucose monitors for diabetes or ECG monitors for people with cardiac problems, but guessing a market size of $40-$60 billion today, projecting to grow to well north of $100 billion by 2030 seems quite safe. Companies continue to develop more and new ways to collect your health data—Apple’s recent announcement of their newest AirPod Pro 3, for instance, includes heart rate monitors in the earbuds!

Selling the devices is one thing, but having access to all of that sweet, sweet data is another incentive. Reading the privacy policies for a few large wearables companies like Fitbit (owned by Google) or Oura, I can confirm that these companies state they do not sell user data to third parties. Frankly, though, it is unclear how and if the companies could use this data in training AI models, a more recent concern. But even if the companies pinky promise they are being responsible with your data, as noted in a research report released by Mozilla last year, the data is still vulnerable to security breaches, handling by third-party vendors, and probes by governmental authorities. Examples of sloppy or negligent security abound.

Insurance companies want in on the action too. More health data means better actuarial predictions by the insurance companies, perhaps someday leading to the insurance holy grail of the personalized premium. My health insurer, Aetna, offers discounts to buy and monetary rewards for connecting biometric devices to their insurance app. While it’s all carrots for now, providing gift cards for hitting a certain step goal, for instance, there are limited legal protections preventing the companies from turning to the stick. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, for instance, prevents insurers from discriminating against people based on their genetic information. So while your insurer can’t deny coverage to someone with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy because of a read of their genome, nothing is stopping them from noticing their smartwatch is registering consistent atrial fibrillation, a lower-than-average amount of exercise, and distorted recovery times and connecting the dots. And to go back to the previous section, what if the devices aren’t accurate, but users are nonetheless financially penalized for “bad” biometric readings?

Fitness tracking makes exercise no longer an end in itself, or even a means to fitness, but rather a means to social status. Is this bad? Not necessarily. But I’ve seen it cause FOMO and even tendencies to overexercise in an unhealthy way in myself and others (in the Boulder bubble in particular).

Two months later and while the leg lump is still present, nothing bad has happened.

I take my Coros Apex 2 Pro off when I climb hand cracks. I also take it off when I climb finger cracks. I tend to leave it on when I'm sport climbing. It has no clue what I'm doing when I go rock climbing.

My watch also has no clue that I'm grilling right now, which sucks, because my stress levels are going way down. All in all, a flawed tool at best, and as you suggest, insidious at worst.

In all seriousness, this argument could likely be expanded to all things that flood us with metrics and pressure to gameify them (social media, substack engagement, SLOS vs SLOP attendance etc...). I think I'll move to a cabin in the woods without wifi, minimize my social interactions, and try to set a PR on how many times I can read Walden each week.

Agreed that there's not much signal you can get from the noise, but I have been finding drops in HRV helpful to decide if I'm reading for a loading day in training or not.