Valuable, but not productive

Consulting & finance as black holes of elite human capital

In my second year of college, my scholarship program hosted a two-week long retreat dedicated to student enrichment. I, along with the other 35 scholars of my class, attended career workshops exploring teaching, engineering, and business. We took a public speaking course and etiquette class. We volunteered together at the local Boys and Girls Club. We completed a ropes course and other team-building activities. Most importantly, we got to know each other.

These activities made sense. They were a cohesive offering for a university’s merit scholarship program to provide to its students. That week created friendships and memories that I treasure.

One component of the program stood out as a bit weird to me at the time, though, and time has only made its inclusion feel stranger: the Consulting and Finance career coaching.

Sure, there was a third option: Immersion, “for students still investigating various career pathways.” But the fact that Consulting and Finance received their own specific career coaches, curricula, and a complimentary four-week bootcamp to sharpen technical skills and case interview abilities sent a message to us: these are career pathways that people like you take. It sent that message strongly enough that I found myself signed up for the Consulting track despite not knowing what Consulting was.

By “people like you” I mean people who have lived their lives exactly as they were supposed to live them on the rails of traditional achievement. These people received perfect grades through high school and aced the SAT. They were talented athletes, or gifted artists, or both, and involved in making their communities better. They were class presidents, Eagle Scouts, or published researchers. They were accepted into elite colleges, receiving scholarships, honors, and awards.

In some ways, the end of college marks the end of this traditional path. Post-graduation, these precocious youths might hypothetically go in any direction. Maybe they continue their education—going to law school, med school, or obtaining a PhD. Perhaps instead they jump straight into industry or working in government. Some might pursue entrepreneurship. Others may work stints with groups like Teach for America, the Peace Corps, or AmeriCorps. I know people that have done all of these things.

Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom, though, and a talented, ambitious, but uncertain youth feels that anxiety with acuteness. That likely explain why the modal path for these most promising of graduates is to go into consulting or finance.

Investment banking. Private Equity. Management Consulting. These jobs are lucrative—extremely lucrative. They command the highest compensation rates of any industry, especially for those at the top firms—the Big Three consulting firms and the bulge bracket banks of the world.

Perhaps more importantly, these jobs confer a dose of automatic respect and a place to channel ambition. As David Brooks wrote, “it’s competitive, so it must be good,” so students from top 25 universities (these firms only recruit the best, after all) join up in droves.

These industries, especially consulting, sell themselves as the natural next step for the liberal arts student who doesn’t know what’s next. Consulting, so say the recruiters and boosters, is applied critical thinking, after all.

I’m not totally naive. Money talks. Sometimes, people just want to collect their bag. Especially for those that take on debt to go to school, I can’t argue with that. But the truth is that if you’re at a top 25 school, you’ve already made it into the elite, and if you’re coming from a disadvantaged background it’s unlikely you’re paying anything to attend these schools. And the data suggests that people from backgrounds rich and poor alike choose these industries.

Schools want prestigious and wealthy alumni networks; consultancies, banks, and finance shops are more than happy to provide this in exchange for the brains and time of their best and brightest. Thus, the sponsored career fairs, the access to the university mailing lists, the meet-and-greet networking sessions on campus not only persist, but propagate.

Those taking the plunge often talk about the exit opportunities, or point out how their employer will pay for their grad school in exchange for just a couple more years at the Firm. Lifestyle creep, golden handcuffs, social expectation, developed risk aversion, that desire to continue striving for just one more promotion, one more bonus, soon I’ll make partner. With these pressures, it’s easy to rationalize joining up or staying in the game.

I struggle to articulate exactly what about the work itself leaves a bad taste in my mouth, but the stranglehold that these industries hold over elite graduates saddens me. Maybe our society is overproducing elites and these industries sop up the excess. But it’s my personal experience that it’s the very best that end up in these jobs.

I won’t claim that there isn’t immense economic value in the services that consultants, traders, and investment bankers provide. I’m also going to be generous and not make the claim that consulting and finance are morally wrong—though there exist plenty of people who have argued quite convincingly that these careers represent a weaponization of the liberal arts. In particular, this article’s thesis is compelling: “To justify McKinsey as essentially benign is to justify the violence of the current world order. It’s not just critical thinking and spreadsheets.”

Instead, I can’t stop thinking about how these industries aren’t productive in a social sense. They aren’t generative. They are valuable, definitely, and you’re compensated accordingly, but I’m not sure that they create social value. At a hedge fund or a management consultancy you aren’t producing anything. You aren’t building. There is no product. There is no real legacy of your work beyond ledgers of trades, stories of past deals, and folders of impeccably-formatted slide decks.

I feel counterfactual dread. What could these individuals be doing instead? Traders at Jane Street who majored in physics look for arbitrage opportunities instead of looking for the theory of everything. Bain and McKinsey consultants improve widget production and design optimal layoff strategies rather than become entrepreneurs, researchers, artists, or doing work involving whatever actually motivated them to major in philosophy, history, or biology.

I wonder about the physical and emotional costs. Burnout is real. Despite the first-class travel benefits and fancy dinners, the demands of these jobs ruin people. You can’t maintain relationships, your physical health, and sleep enough when you work that much. I have friends who work in these roles that I haven’t seen in years because they’re onsite four days, regularly working for 60, 80, or 100 hours a week in what should be the physical prime of their lives. Furthermore, as noted in The story BCG offered me $16,000 not to tell, “Burning out isn’t just about work load, it’s about work load being greater than the motivation to do work.” Trying hard is good, but if you’re investing that much effort let it be for something interesting, generative, cool.

I value work. I value achievement. And yes, I value financial security. But I also value what W. E. B. Du Bois said in a speech: “Work is service, not gain. The object of work is life, not income.” That is what I lament. I’ve watched some of the most remarkable people I know grind themselves up, or disappear from my social network for years, in exchange for manufactured prestige and a pile of money.

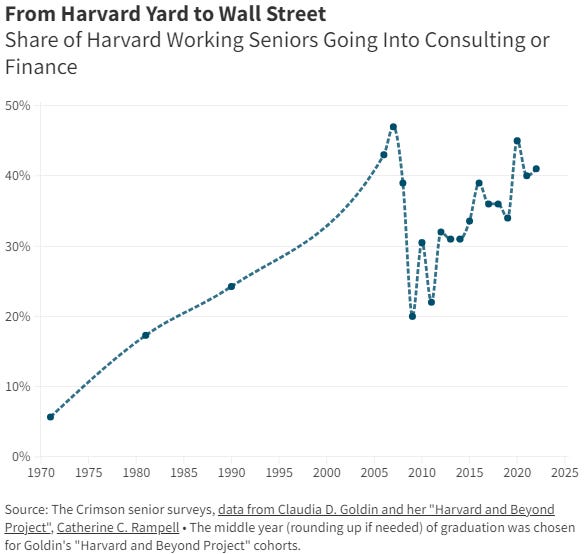

High finance and consulting are like black holes. Every year, a third to a half of the shining stars of our nation’s brightest graduates end up trapped in their gravity wells, from which physicists have long held there is no escape, not even for their luminous light.

In 2016, Stephen Hawking, Malcolm Perry and Andrew Strominger proposed an escape route—a way by which information might be able to escape a black hole. Although the scientific community hasn’t endorsed the researchers’ solution to the information paradox, I do have a few friends who recently have escaped their own black holes. They’ve finally made their exits into things infinitely more interesting than consulting and finance—industry, crypto, social entrepreneurship, writing, AI, solar e-biking across the country. And so, I do endorse Hawkings’ optimism: “[Black holes] are not the eternal prisons they were once thought. If you feel you are trapped in a black hole, don’t give up. There is a way out.”

If you’d like to read a comparison of venture capitalists to backcountry skiers, check this out:

Backcountry Skiers and Venture Capitalists

Both venture capitalists and backcountry skiers know risk like old friends. Both groups have to carefully calculate risk in their everyday life, whether at the office or on the snow. To some extent, risk creates the activity. Without risk, there wouldn’t be outsize returns available to VCs; without risk, as Jon Krakauer noted in the intro, skiing would lack interest and, more importantly to me, meaning...

oof, pretty on the nose. my dad (nerd/scientist, extreme skeptic re: my post-college career choice, 55 years old and crankily battling the unwelcome incursion of management consultants at his lab for the first time) got a HUGE kick out of the title here, so I owe you a beer for that. Made his Monday.

Now, the real question: what's the best way to break down these strongholds and divert people to actually building useful stuff (art, apps, clean power plants)? There's no doubt in my mind that consulting and finance careers are a fast-track to wasted potential. But all of the seductive pull factors you point out in the essay are spot-on, and only get more entrenched over time.

I have a ton of demoralizing anecdotes about former colleagues who were so jealous of my adventures...until they realized exactly how much ramen I was eating, and that I was no longer staying in plush hotels.

Consequently, I think it's more realistic to start the shift when students are still in college, or even before. I'd like to see a world on college campuses where students are encouraged to take more risks / fail more often (e.g., ending crazy Ivy-league grade inflation) because I have a hunch that learned risk aversion plays a huge role in the growth of these careers.

And, more of an emphasis on inherent value of building stuff (even for us liberal arts majors) because I do think 'elite human capital' has lost the plot there, and it shows. But that's a topic for another essay.

As usual, great stuff. Keep writing about exactly what you want to write about - the eclecticism is what makes this blog awesome.

P.S. For what it's worth, I do think the anchoring on finance / consulting to a certain extent reflects an east coast bias. I'd say the supergeniuses I know out in California tend to pooh-pooh this stuff and are much more dialed-in on getting jobs at FAANG/cashing out on the latest SaaS trend - and I have my doubts about how much social value some of this creates. But then again, at least they're writing code, which is more of a product than another PowerPoint deck! :)

what I hear you saying here is that what you find valuable and important ("solar e-biking" etc) is somewhat different from what society as a whole finds valuable and important (as reflected by risk-adjusted compensation, opportunities and prestige, which finance/consulting&tech (and law+medicine) dominate). sounds normal to me, those aggregated revealed preferences of what people are willing to pay for reflected in labor prices (=comp) would typically be different from every particular individual values. people are different, and it's good.

one might try to mount an argument that "social value" created is different from what's earned from the activity (and ultimately reflected in comp) as "value capture" rates across sectors differs, but it's kinda hard to do well as ultimately the market is the best (not to say perfect) aggregator of information on what ppl rly need and want, and every "more ppl should stick to their philosophy majors" cry can be met with "who needs those parasites" cry from another person.

it's tempting and governments around the world keep trying to "prop this industry tax that one", but most economists are probably against those kinda policies as what might seem good is oft not actly much good, and things work better if left up to the markets.

it also seems to me you're a bit unfair re "consulting&finance produce no legacy while tech&industry are so great". plenty an experienced finance folk are proud of "investing in next Zuck when he was 15 and chaperoning him to $10bil val" or "saving Goldman from bankruptcy with an emergency loan during GFC, or, for consulting, for "coming up to clean up this almost bankrupt/dysfunctional mess of a company/division and seeing it rly shine in a couple years". while plenty a techie hates his life coding some GDPR compliance shit, and while most entrepreneurs are gung-ho about their startups, many others don't feel yet another "uber for X with a Y twist" app is changing the world much more than a good ibanking deal. the world isn't so black and white, many people in all sorts of professions love what they do, many don't, some make a huge impact, many don't.

also, it seems you might be a bit biased towards concrete vs diffuse impact, as is common. "Making markets slightly more efficient" boo, "rolling out some dumb new app" yay.