A Certain Slant of Light

Enhancing the sublimity of snow through art

The difference between the best turn of the season and being buried in an avalanche is often just a few degrees of azimuth or an extra hour in the sun. Backcountry skiing has transformed the way I look at a face of snow: the solar aspect, slope angle, temperature, time of day, cloud oktas, the presence of micro terrain features, and a slope’s orientation to the wind affect the snow in nuanced ways. With education and experience, a skier can create a prediction of how the snow will feel given these factors.

As I inspect the snow in more detail, and invest more effort in learning about snow science, I find myself seeing more in the snow. Perhaps it’s the whiteness of the snow bringing to mind a blank canvas, but lately I’ve found myself thinking of my friend from college, Mary Royall, and her art while skiing.

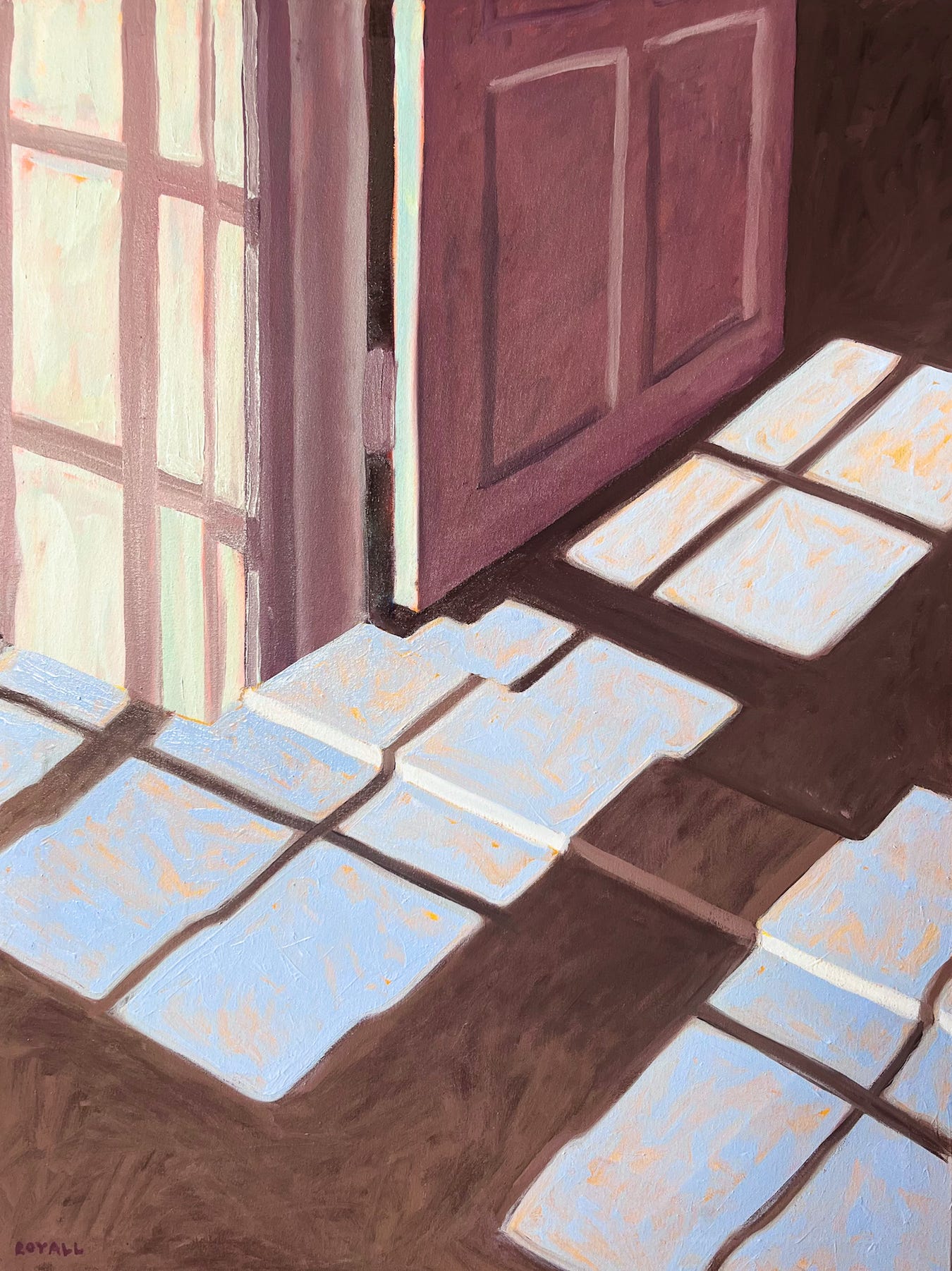

Mary Royall, “a contemporary artist, light chaser, and color enthusiast based in Brooklyn, NY,” has written about a practice she calls “light foraging” where she paints the imprints of light and shadow from trees and then takes them back to her studio to “explore the shape of the light.” Mary Royall has been fighting chronic pain issues for some time and was recently diagnosed with Lyme disease. Upon this diagnosis, she wrote:

In the winter, the leaves have been thinner and the light has been more sparse, but it’s still there. Looking at the light, and bringing it to life on canvas, I’ve realized that it looks exactly like my pain. They are one in the same — organic, sometimes spidery and scarce, sometimes round and whole.

The shape of the light is the shape of pain and joy and fear and love, and all the messy in between things.

Mary Royall is a documentarian of light. To date, she has fixated on the glow of sunlight through the leaves of a tree, or the shadow cast by a windowpane at sunrise, or the reflections of a beam of light through a jug of water. If her muse ever runs dry, though, I think she should look to snow.

There’s a certain slant of light,

Winter afternoons—

That oppresses, like the Heft

of Cathedral tunes…

- Emily Dickinson

The interplay of snow and light is not only of utmost practical importance to the enjoyment and safety of the backcountry skier; learning to understand the snow is like learning to read. There are stories written in every corniced ridgeline and undulating powderfield. Nature hides meaning in leeward drifts, natural slide paths, and sugary facets. These stories are tales of weather, of time, and of movement. Acquiring the literacy to read these stories unlocks not only power, but also new layers of beauty.

Over this past winter, I’ve been conducting my own light foraging every time I’ve gone out skiing. I’ve focused my attention on the snow, its color and shape, the interplay of dark shadow and blinding light and wind and rock and sky. I’m not just saying this for a blog post—I’ve truly had moments where I’ve stopped mid-run and taken my goggles off to absorb everything I could about what I was seeing in the snow.

I absorbed how crystalline powder glitters like diamonds under a bluebird sky:

I observed the albedous glow of moonlit snow illuminating the night as well as any lantern:

I saw jagged alpine rock contrast with the pure white of corniced snow on a ridgeline. I noticed how shadows cast by the overhanging ice, the rock, and deposits of wind-drifted snow paint lines on the massive canvas of the mountain just as granules of ice carve miniscule sculptures across sastrugied snowfields.

A primary motivation for my time spent in the mountains is in experiencing the sublime. Viewing Mary Royall’s art has helped me articulate a new way to experience the false mundanity of a gust of wind throwing snow into my face, clouds passing over the sun, and purple alpenglow kissing a ridgeline. There is information and meaning in each of these unassuming occurrences—it’s up to you to find it.

For more beautiful photography from my friends, and thoughts on dryness rather than snow, see this post:

Aridity Incarnate

The landscape here in the West is sharper than in my native Appalachians. The mountains are younger, more jagged. There are fewer trees to smooth out the ridgelines. While the artist paints the Appalachians in cool colors—green leaves and ferns and mosses, smokey blue mountains on the horizon, soft brown carpets of deciduous leaves—the palette of the We…