Aridity Incarnate

The American West, Fiction, and Water

The landscape here in the West is sharper than in my native Appalachians. The mountains are younger, more jagged. There are fewer trees to smooth out the ridgelines. While the artist paints the Appalachians in cool colors—green leaves and ferns and mosses, smokey blue mountains on the horizon, soft brown carpets of deciduous leaves—the palette of the West is warm. Red sandstone cliffs and orange-streaked granite. Alpenglow. Yellow aspens. Muddy rivers. Red sunrises, red sunsets.

I’ve been spending past-due time with some of the Western canon of stories and history—to be clear, the North American Western canon. Tales of Texas, the Rockies, Mexico, mighty rivers, great plains, sagebrush and horses, Comanche and Lakota and Ute and Arapaho.

As pointed out by my friend Jake in a recent email, “the ‘American West’ or ‘the West’ is a mythical space. In other words, it didn't exist. The works of Lonesome Dove and McCarthy are closer to fantasy than they are to history.” Despite their false verisimilitude, these stories still convey a truth: the story of the white American identity and what it valued and aspired to during the extractive, genocidal, “manifest” expansion across the Plains to the Pacific.

An aspect of this truth I noticed is the landscape acts as a character itself in these stories. Usually an antagonist, or, at the very least, not an ally. From the limitless emptiness of the prairie to mountains that stretch to heights beyond comprehension, the landscape provides physical and metaphysical context to the other characters in Western stories. The human characters seem small and unimportant; the character of the landscape wields vastness and eternity. Even the sky feels bigger in the West.

The landscape often conflicts with the other characters over water. Sometimes there’s too much, but usually there’s not nearly enough. Earth-shattering storms, with drowning flash floods, miserable cold and wetness to set teeth chattering, and deadly lightning challenge our protagonists day and night alike. Swollen river crossings present fearful, fatal obstacles to even the most seasoned cowboys.

Under the relentless sun, dryness and thirst represent the most common motif. Where is the nearest water? Where can we water the horses? Is there any water left in that canteen? Is the copse of cottonwoods on the horizon the mark of a spring or a mirage?

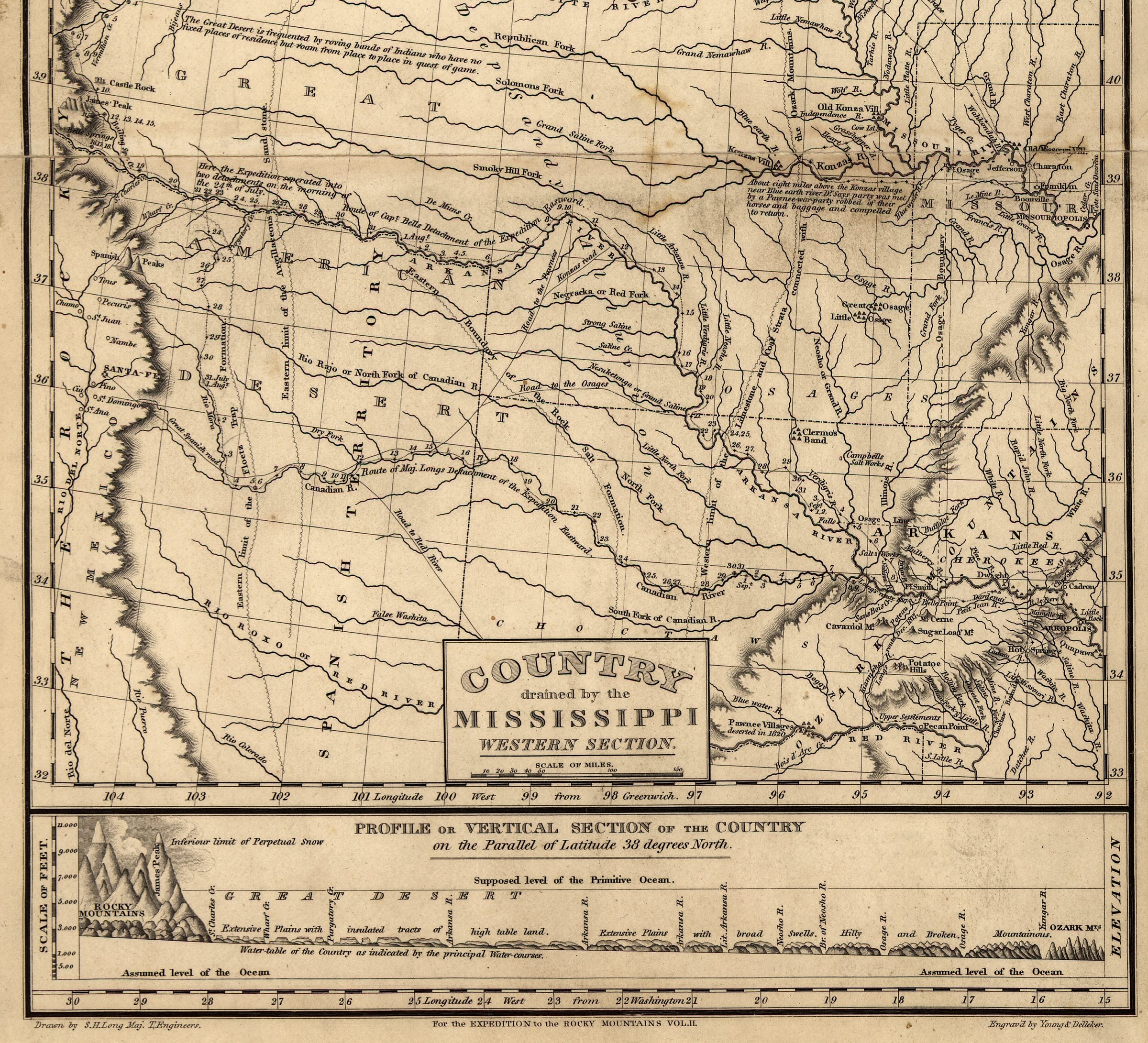

Stephen H. Long, leader of the 1820 expedition to explore the West, christened the land stretching from the eastern boundary of the Rockies to the 100th meridian cutting through the Dakotas, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas the “Great American Desert.”

Long’s expedition geographer wrote in 1822:

I do not hesitate in giving the opinion, that it is almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course, uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence. Although tracts of fertile land considerably extensive are occasionally to be met with, yet the scarcity of wood and water, almost uniformly prevalent, will prove an insuperable obstacle in the way of settling the country.

Yet this prophecy proved superable. Not only do millions of people now live in the Great American Desert; people farm it. Technology, irrigation, dams, and Midwest determination refuted the region’s barrenness. In a telling illustration of the “indigenous optimism of the West,” the Colorado Historical Society’s overview of the idea of the Great American Desert has a smug section entitled “Birth of a Myth.”

Some thoughtful folks remain concerned, nonetheless. In a 1991 essay, Wallace Stegner wrote (emphasis mine):

Historically, irrigation civilizations have died, either of salinization or of accumulating engineering problems, except in Egypt, where, until the Aswan Dam, the annual Nile flood kept the land sweet. And if there are no technical reasons why we cannot move water from remote watersheds, there are ecological and, I might suggest, moral reasons why we shouldn’t. As a Crow Indian friend of mine said about the coal in his country, “God put it there. That’s a good place for it.” Lots of things have learned to depend on the water where it is. It would become us to leave their living space intact, for if we don’t, we take chances on our own.

Sooner or later the West must accept the limitations imposed by aridity, one of the chief of which is a restricted human population.

The West has a water problem. The Colorado River was doomed to be overdrawn from the day they drafted its budget based on exaggerated figures of its flows. I’ve read Cadillac Desert. Water rights, especially the prior appropriation doctrine, create a misincentivized legal and economic conflagration to rival a Western wildfire. Agricultural use of water remains particularly nonsensical.

Even still, my natural proclivity is to ignore doomerism. Writers since Malthus have hemmed and hawed over overpopulation and resource use, yet technology has always proved their concerns overblown.

I’m not convinced of the physical impossibility of transforming the West, for Arthur Clarke’s Three Laws come to mind:

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Stegner was a writer, not a scientist, but in 1991 he certainly was both distinguished and elderly. Was he not very probably wrong? Why can’t we turn the Great American Desert into a land of plenty? Have we not already proved Stephen Long and his expedition wrong in calling the West a desert? And yet…

When I first sat down to collect notes on this topic, I felt like battling against Stegner. But a few weeks and a few Cormac McCarthy books later, and I find myself more convinced by his Crow friend’s moral argument against conquering the West’s dryness. I don’t doubt we can do it, but perhaps we shouldn’t.

Spending time with these authors and their Western tropes—the cattle drives, gunfights, prairie fires, breaking horses and riding them across terra damnata, drinking whiskey in saloons, crackling campfires, skies overflowing with stars—I’ve become certain that dryness is the essential character trait of the Western landscape. I see it in these pages and I see it in my everyday life.

Thirstiness creates not only an ecology, but a people, a culture, a way of thinking. The origins of America’s relationship with the mythical West, problematic as they remain, are our inheritance. Ignoring the limits imposed by aridity wholesale betrays the Western landscape and condemns us to continue fighting it as an antagonist in this ongoing story.

I don’t want to lose my technocrat’s optimism. I still believe in improvement, technology, and ambition. I want to believe in the indigenous optimism of the West. Perhaps coupling these motivations with more of a Land Ethic wouldn’t hurt, though.

Musical inspiration for this post provided by Jake’s Public and Wild playlist.

A delightful tribute to a uniquely American landscape and the writers who've grappled with it. ! A modern addition to the canon of the (south)west I'd propose is a scifi book called The Water Knife. A near-future thriller with a little bit of Cadillac Desert and a lot of thirstiness.

I was around 36 when I consecutively read Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy. I was transported. I have yet to meet a woman who has read the series and I’m curious if there is something gendered about the way men and women experience the writing. There is a kind of intimacy embedded in the silent solidarity of the protagonists with the backdrop of a vast desert expanses … I wonder if it tends to be more appealing to men for whatever reason.

I assume that the more we experience abundance, the more we’ll yearn for scarcity. We may choose to live in places like Singapore, San Francisco, and Mexico City, but we’ll daydream about (and pay good money to visit) the rugged wilderness of simplicity and inconvenience. As the world’s wealth expands and the population declines, I assume that more billionaires will support nature conservancy.

And I imagine that *some* desert landscapes like Las Vegas and the UAE will take advantage of solar + desalination to astroturf big sections of desert with lots of golf courses and manicured gardens. Those aren’t places for me, but I’m happy they’ll exist for whoever enjoys them.