As I scrambled down the granite slabs that form the summit of Bear Peak, Jack told me to hold up so he could grab a photo. I perched at the top of a rock like a bird, waiting. He gestured behind me to some ladies clambering down the final slab to rejoin the trail, implying he was waiting for them to clear out of the frame. “Creating the illusion of solitude,” I say, looking out to the northeast at the town of Boulder, then panning to the south where the skyscrapers of Denver were visible on the horizon.

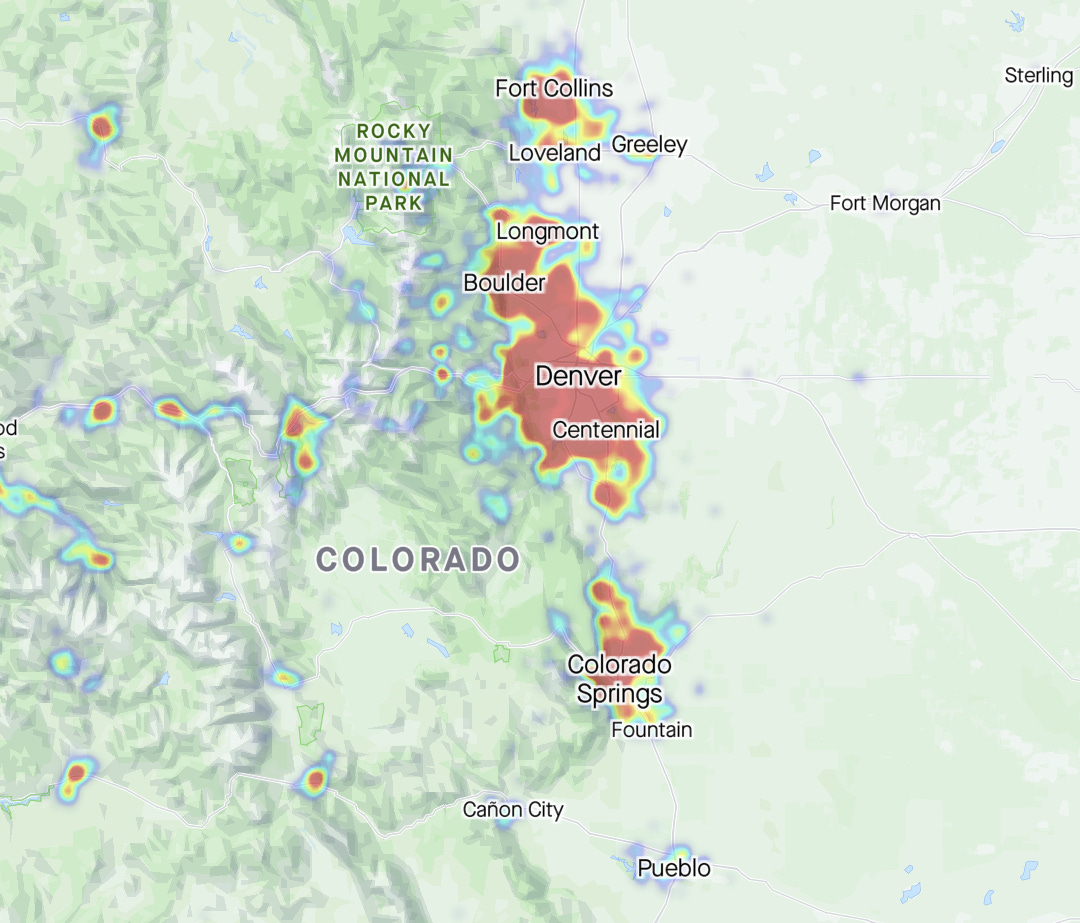

Here in the Front Range, we still seek peace through solitude despite sharing the landscape with something like five million other people. On our long run that day, even as Jack and I traversed trails for miles at a time without seeing a soul, we still ended up crossing paths with dozens of people. At any given time, we were only four or five miles from downtown Boulder.

Just as Jack’s photograph created an illusion of solitude in the midst of a crowd of recreators, the typical conception of wilderness reinforce a beautiful but false narrative of purity. William Cronon’s essay The Trouble with Widlerness; Or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature convincingly claims that our seemingly-innate love of wilderness is a cultural invention, and a recent one at that. People characterized Wilderness as something to fear and avoid, a punishment from God dished out as payment for original sin, as recently as the 19th century.

Writers of the sublime and the transcendental began the cultural reformation of wilderness in the midcentury—writers like Thoreau and Wordsworth taking the first steps toward a sort of nervous, fearful awe, with folks like John Muir completing the transformation to admiring ecstasy.

The elite’s emerging passion for wilderness in 19th century reflected a belief in wild land as an alternative to “the ugly artificiality of modern civilization. The irony, of course, was that in the process wilderness came to reflect the very civilization its devotees sought to escape.” At the time, it was the genteel city folk that eroticized wilderness, whereas “country people generally know far too much about working the land to regard unworked land as their ideal.” Not to mention the ridiculous erasure of the native people that lived in the ‘untouched’ lands for thousands of years before their genocidal removal.

This conflict continues today in the arguments about land use between the people who live there, the Sagebrush Rebel types who value land for productive and extractive uses, and people in cities who value wild lands primarily for recreation.

The dream of an unworked natural landscape is very much the fantasy of people who have never themselves had to work the land to make a living—urban folk for whom food comes from a supermarket or a restaurant instead of a field, and for whom the wooden houses in which they live and work apparently have no meaningful connection to the forests in which trees grow and die. Only people whose relation to the land was already alienated could hold up wilderness as a model for human life in nature, for the romantic ideology of wilderness leaves precisely nowhere for human beings actually to make their living from the land.

Cronon’s key point is that conceptions of wilderness that create a Manichean split between Good Untouched Nature and Bad Developed Land cause us to believe that we are separate from nature, when in reality we are always a part of it. He wants us to declare with Thoreau “‘in Wildness is the preservation of the World,’ for wildness (as opposed to wilderness) can be found anywhere: in the seemingly tame fields and woodlots of Massachusetts, in the cracks of a Manhattan sidewalk, even in the cells of our own bodies.”

Thoreau, one of the progenitors of the false dichotomy of Wilderness, infamously had his mother do his laundry during his two years, two months, and two days living at Walden Pond. I imagine that Cronon, rather than condemning this practice as hypocrisy against Thoreau’s project of self-sufficiency and independence, would instead see it as illustration of the falseness of Wilderness as pristine and nonhuman. Thoreau’s outsourcing of domestic chores, rather than a disqualification of his observations on wilderness, is proof that wildness can be found everywhere.

Last week, I was in New York City for work. One afternoon, I ventured out from Midtown for a run in Central Park. The quantity of people there and the variety of things they were doing boggled the mind. I passed walkers and was passed by runners; skateboarders, bikers, rollerbladers, and scooters rolled down the paths; horse-drawn carriages full of tourists and bored-looking drivers doddered up the street. Here, there was no physical solitude, and definitely no untouched virgin land, as much as that exists anywhere. Yet thousands were still out searching for the solitude you can find in your mind and for a touch from nature.

I’d never live in New York. But running under the canopy of amber autumn leaves, watching tourists photograph squirrels scurrying up ancient oaks, seeing the stubborn grass poke through the cracks of Manhattan sidewalks, I couldn’t help but think that the city wasn’t all artificiality. Wildness can—must—be found anywhere. Just as Thoreau found Wildness at Walden Pond despite his frequent visits to nearby Concord, we can find Wildness in the Front Range as easily as in New York City.

For other recent thoughts about land use and the West in particular, see Aridity Incarnate: