UPPERCASE lowercase Andinbetvveen

On stylized titling: the expanding canvas of musical expression

You can find a playlist of every song and artist referenced in this article here:

I. Differentiation

The barriers to entry have never been lower for a musician; anyone with a microphone, a computer, and an internet connection can upload their music to Youtube, Soundcloud, or any of the many other streaming services.

With these low barriers to entry, we now see unprecedented competition in the music industry. There are so many small musicians trying to eke out a living from their art that we are seeing revolutions in music business models to unlock more revenue for artists.

For example, over the last decade Vulfpeck has engaged in some of the more interesting and innovative business model experiments in music. Long-time critics of streaming services like Spotify, Vulf created a silent album, Sleepify, and got their fans to stream it constantly while they were at work or asleep, earning Vulfpeck enough money from streams to fund some free shows. For their most recent album, The Joy of Music, the Job of Real Estate, Vulfpeck auctioned off one of the tracks on Ebay to the highest bidder (the winning bid was $70k). Vulfpeck’s social media accounts regularly post screenshots of excel spreadsheets showing their vinyl’s financial returns over time as collectibles. Their unique approach adds an eclectic charm to the band that is only accentuated by their music and live performances. See the below compilation of their classic funk banger, “It Gets Funkier”, but every time it gets funkier, it gets funkier.

With this clear need for differentiation, I find it unsurprising that artists are expanding their creative canvas beyond the music itself. Like the expansion of artistic expression that occurred with the growth of album art, changes in technology have both enabled and made necessary an expansion of artists’ domains of expression to include the stylized titling of their band names, songs, and albums.

When vinyl was the medium of choice, album art became a pivotal part of the experience of music that likely declined in importance as cassettes and CDs, with their smaller display area, increased in popularity. With the rise of streaming, the ability to purchase songs a la carte changed how fans interacted with music, decreasing the importance of the album as a unit of analysis compared to the hit single. Now, with online streaming as the dominant method of consumption, artists are faced with a new set of incentives to optimize for in their art and its marketing.

When songs were primarily consumed on the radio or by physical copies, the spelling or capitalization of the track list wasn’t relevant—you would practically never see it! Now, as songs are primarily consumed in playlists and displayed on phone screens, the appearance of the titles of the artist, album, and song have never been more relevant or important.

II. Spe11ing

When you Google a band, it can be difficult to find what you want in the search results if the band shares a name with something mundane. Groups like CHVRCHES, NxWorries, or Alvvays realized this fact and changed the spelling of their names to stand out in search results. Googling “CHVRCHES” versus “CHURCHES” is a form of search engine optimization deliberately built into the band’s name for that purpose.

III. UPPERCASE

Another facet of CHVRCHES is the all-caps spelling of the band. When scrolling through a list, the capital letters make a band name pop and stand out relative to their lowercase counterparts. Many musicians have played with the spelling of their band names, most often in the hip-hop genre, for not only the purposes of standing out but more often for thematic purposes.

MF DOOM made it clear that his name was always to be shown in “All Caps”: “Just remember ALL CAPS when you spell the man name.”

BROCKHAMPTON, KAYTRANADA, BADBADNOTGOOD, JPEGMAFIA, JID, REASON and JAY-Z, among many others, are hip-hop artists or producers that are in the all-caps club.

The all-caps convention is a statement by the artist regarding the intensity of their music. It provides emphasis. Some of the artists listed above, like BROCKHAMPTON, make their entire discography of song and album names use the uppercase style. Other artists employ uppercase at the album-level. ALL AMERIKKKAN BADA$$ by Joey Bada$$, a phenomenal, intense, and rich album about racism and the black experience in America, has all its songs in uppercase. Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer prize-winning masterpiece, DAMN., is also in all-caps, as is Vince Staple’s self-titled new album. Recently-disgraced Travis Scott played with capitalization on his ASTROWORLD album (and lowercase on earlier albums).

Sometimes, single songs are highlighted by their capitalization. A model example is Kanye West’s “POWER”, the lead single off the 2010 mega-classic My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. As outlined in (honestly way too much) detail in Dissect, “POWER” was Kanye’s first release after his Taylor Swift VMAs disaster, and in stylizing the song with all caps he signified his defiance and that Kanye was back. The song is peak Kayne: egotistic, braggadocios, swaggering, and full of self-confidence, anchored by the hook “No one man should have all that POWER.”

Power

power

POWER

You can’t listen to the song without agreeing that all-caps was the way to go here.

IV. lowercase

Billie Eilish’s WHEN WE ALL FALL ASLEEP, WHERE DO WE GO? (2019) takes a different tact; the album name is capitalized, but every song is lowercase. Billie’s album, which I only recently listened to for the first time, is so understated—the songs and production are measured and modest enough that the lowercase feels appropriate—but there are enough moments of ambition and boldness (e.g., 0:37, 0:35, 0:59) to necessitate the emphasis provided by the album name’s capitalization.

The lowercase convention, also employed by folks like Ariana Grande and Taylor Swift on albums, and other artists like slenderbodies across their name and discography, copies the aesthetic of turning off autocorrect. Just as it gives texts or tweets a casual air, the lowercase vibe is right at home with a lot of folky, acoustic, or stripped-down music.

This 𝖆𝖊𝖘𝖙𝖍𝖊𝖙𝖎𝖈, if you will, can also represent a minimalist mood or a song’s unpolished nature. My favorite example of this is Kendrick Lamar’s untitled unmastered. (2016), a collection of demos from his 2015 effort, To Pimp a Butterfly. Kendrick also used this stylization for a couple of songs and the album name of good kid, m.A.A.d city (2012).

Some artists don’t commit to any convention. The 2019 album Now, Not Yet by half•alive plays with every capitalization strategy possible, along with the • symbol in their lowercase name. Another symbol reference, alt-J (∆ when pressed on a Mac keyboard) has a couple of songs with stylized titles like “3WW” or “U&ME”, the lead single off an upcoming album.

Lana Del Ray’s Norman fucking Rockwell! (2019) utilized sporadic capitalization with many of the songs, such as the title track “Norman fucking Rockwell” and the final track, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have – but i have it”, causing mock anguish for some fans due to the irregularities contained within the album. Other artists have caused real frustration with their avant-garde titling; Childish Gambino’s 2020 album 3.15.20 contains songs that are mostly just timestamps. This decision made looking up the songs on this album—or remembering which one you even want to look up, for that matter—difficult and annoying for fans. Artists, tread carefully!

V. Andinbetween

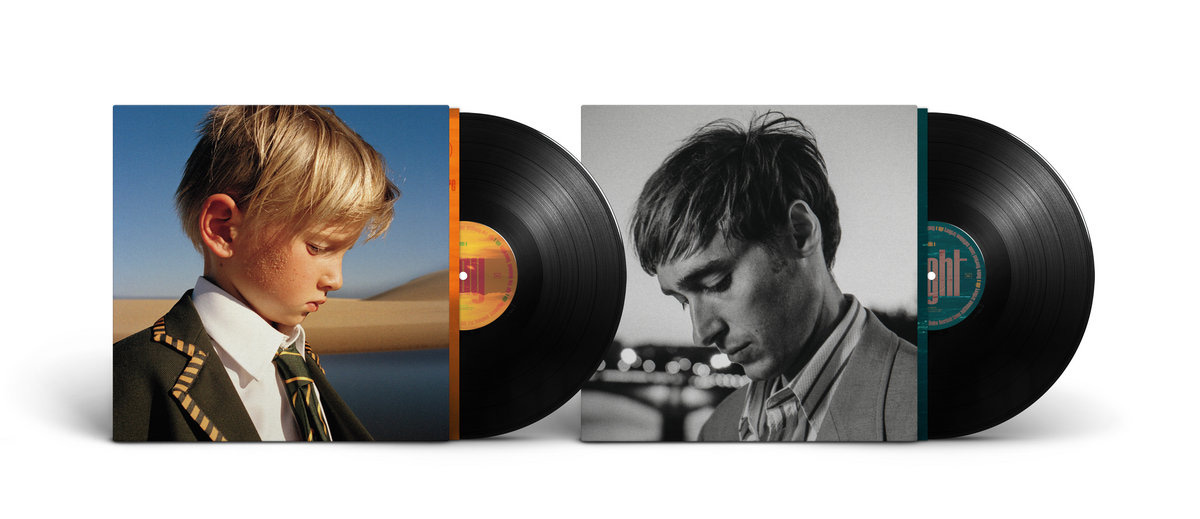

To conclude, I’d like to discuss Day/Night, an album released by the Australian band Parcels on November 5, 2021. Parcels is a 5-piece, self-described “blend between electro-pop and disco-soul” group that rose to prominence after Daft Punk produced one of their songs, “Overnight”. Parcels, for each of their songs, removes all spaces between words, giving us titles like “Tieduprightnow”, “Somethinggreater”, and “Withorwithout”.

In thinking about what might have inspired this stylization, I thought about how the vocals, coupled with the funky beats and innovative composition, flow together in an airy delivery. The lyrics of each song in their full context really do sound like a single word. Curious to check my intuition, I looked up interviews with the band to compare their reasoning to mine. This time, at least, it really is a mundane explanation that wins out: when Parcels was recording their first songs, they used a laptop with a broken spacebar.

“When I bounced down all the demos, there was no space in the title. We would always be communicating on Facebook or whatever, and the guys could always decode my long one-word messages,” noted Patrick Hetherington, keyboardist. “We ended up leaving it in… I could talk about how it represents unity and whatnot, but it’s a broken spacebar.”

They continued this pattern on Day/Night but with an added twist. The album is, unsurprisingly, divided into two parts: day and night. The two parts are signified by two capitalized songs: “LIGHT” and “SHADOW”. Jules Crommelin, guitar and vocals, said “We really struggled trying to bring everything into the middle, so two albums meant we could go more organic, lighter, positive and soft for ‘Day’ and then for ‘Night’ we could go deeper and darker. It brought so many ideas from the strat, from songwriting to producing; we could go into this deeper space. It’s such fun.”

Stylization of typography because of technological change and artists following incentives to market themselves effectively in the world of digital music consumption; as a marker within an album; as a tool to provide emphasis or make a statement; as a way to build ~a n a e s t h e t i c ~; as a happy coincidence from a broken keyboard.

Thanks to Lexi, Austin, Arthur, Katie, Robert, James, Maggie, and Irene, and anyone else who I forgot to mention, for sharing UPPERCASE, lowercase, andinbetween songs with me. The instagram music requests don’t miss!

Special thanks to my man Walker Robinson for feedback and ideas on this topic.