Tipping is Spreading and It Sucks

Every tip given in the United States is a blow at our experiment in democracy.

“Oh yeah, sorry. Just one more screen to click through here.”

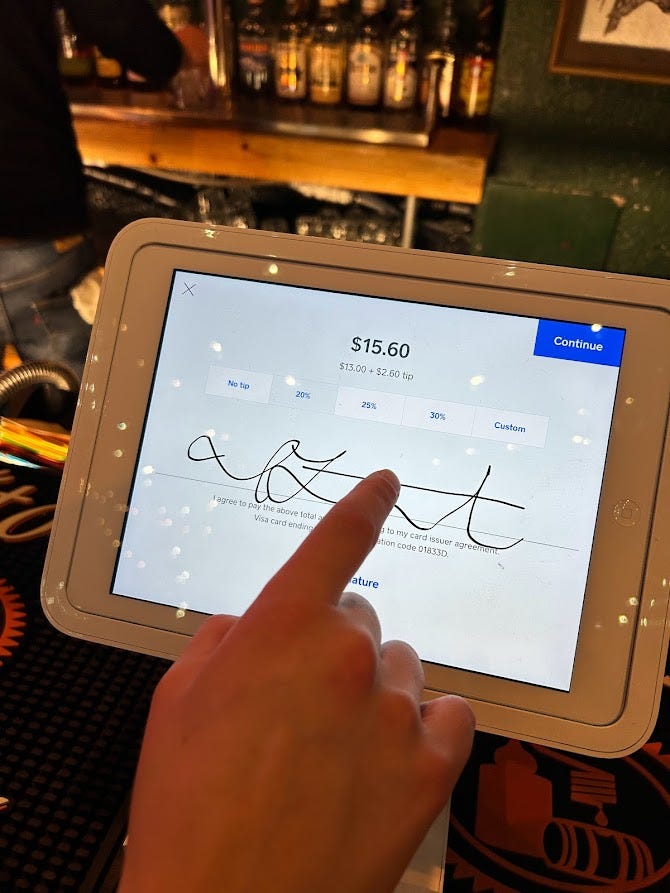

The cashier adeptly flips around the touchscreen of the point-of-sale terminal. The screen has, pre-selected, a 25% tip option. The other options are “20%”, “30%”, and “Custom.” I sigh.

I’m picking up my food from a Thai restaurant that only does takeout. I don’t think I should tip—after all, what am I tipping for? There is no server or delivery person involved. I’m just ordering the food. Where would this tip even go? Is the business even obligated to pass it onto the employees in the kitchen?

I glance at the bowl full of mints next to the register, wondering if that’s what justifies a tip.

I go to confirm my transaction but my finger hesitates over the payment button. “Those bastards almost got me,” I say to myself. Distractedly I had almost accepted the payment with the 25% option pre-selected. I hit “custom” and zero out the tip, feeling the eyes of the person behind me in line burning into me. I grab my food and quickly leave the restaurant, thinking back to my recent post about the phenomenon of drip pricing. I feel that, again, an anti-customer practice is taking root in the food industry.

As I consider the problem, though, I realize that tipping is proliferating across more than just food joints: while tipping has always existed at sit-down restaurants, it has expanded to fast-casual dining, smoothie cafes, ice cream parlors, coffee shops, ride-sharing and delivery apps, car washes, and even retail establishments. Companies both large and small, from Starbucks to your local coffeeshop, are making tipping increasingly salient parts of the customer experience.

What industry is next!

How and why did tipping shift from a jar full of spare change to digital ubiquity? And what is the social impact of tipping’s spread?

(And in case you miss the ol’ tip jar, the startup DipJar has you covered: a tip jar for credit cards. God I love capitalism)

Perverse Incentives, Dark Patterns

Point-of-sale (POS) service providers like Square, Toast, and Clover have revolutionized the way small businesses engage in transactions. They have democratized access to credit card processing to such an extent that I feel more likely to see signs at registers declaring “no cash accepted” than the signs stating “no credits cards” or, especially, “NO AMERICAN EXPRESS” that I remember from my childhood.

As a part of their service package, these POS vendors all have included tipping options at checkout. Many of these tip screens have deceptive user interface design intended to trick or influence users into tipping, called dark patterns.

Dark patterns are common in web and app design and often appear in the context of email subscriptions; here are a dozen different dark pattern-related strategies. Dark patterns abuse our expectations about how webpages and apps should work to funnel our decisions against the user’s interests.

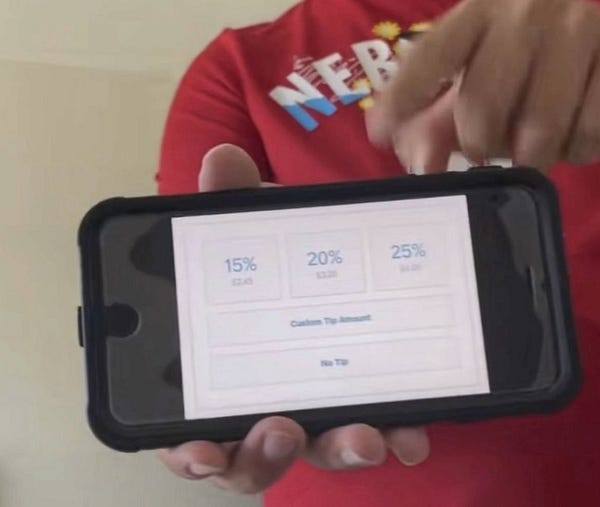

The dark pattern I encounter the most with POS terminals is in button design: the colors of the active button will be switched or the POS terminal’s preferred option will be pre-selected in a way that encourages you to tap through without being aware of what you’re agreeing to pay.

See this example below of how color can impact your choice. If you’re in a rush and quickly tapping through a menu, it would be easy to fail to notice that the 20% option was selected here:

The dreaded turn of the POS tablet also brings social pressure. The customer feels the stare of the cashier, or perhaps wonders if the customers behind them in line will think less of them if they don’t tip. The publicity of the tablet’s screen weaponizes our social awareness to compel tips.

A final way that these companies abuse psychology to squeeze more pennies out of customers: Many POS providers offer differential user interface options based on the total order price—for amounts under $10, for example.

Let’s say you buy a coffee for $4; the terminal will offer $1/$2/$3 tip options instead of 25%/50%/75%. Suggesting a 50% tip on a $4 coffee purchase is gentler when it’s framed as a nominal “$2.” For orders over $10, the options will instead be, say, 20%/25%/30% or custom.

Square calls this “Smart Tip” mode. I don’t disagree that it’s smart (for Square), but it’s annoying and slimy.

Why do the POS companies employ these dark patterns? Cui bono? Examine the following graphic helpfully provided by Toast:

Does it make sense now? The POS companies get a cut of your tips. They’re incentivized to increase the prevalence of tipping because tips increases THEIR revenue.

Square or Clover’s cut of your tip might not be much to you, but it’s enough in aggregate for them employ dark patterns to increase tips.

A Penny for Your Thoughts, a Dollar for Your Looks

Tipping is not just an annoying way that companies use customers to subsidize the wages they pay their employees. Tipping is also an unfair and demeaning way to transfer wealth.

In 1916, William R. Scott published the most famous denunciation of tipping in history: The Itching Palm, A Study of the Habit of Tipping in America. This tour de force, which frames the epidemic of the Itching Palm as an existential threat to democracy, wonders in its opening remarks how such an un-American practice of tipping ever took hold:

If it seems astounding that this aristocratic practice should reach such stupendous proportions in a republic, we must remember that the same republic allowed slavery to reach stupendous proportions.

The mention of slavery, it turns out, is an apt comparison. Tipping came to the United States after the Civil War. Previously, opposition to the practice focused on its European feudal origins; tipping was deemed un-American and aristocratic. After millions of enslaved peoples were freed after the Civil War, however, there were millions of people without work and business owners exploited the newly-liberated labor supply. Restaurants and railroads ‘hired’ workers at either pathetic wages or no wages at all (see the infamous Pullman rail cars for the most egregious example). These former slaves instead had to survive off of tips.

When the New Deal passed the first minimum wage law in 1938, restaurants got an exclusion from having to pay the 25 cent minimum wage. Tipping was here to stay, Scott’s critique be damned:

The moral wrong of tipping is in the grafting spirit it engenders in those who profit by it; in the rigid class distinctions it creates in a republic; in the loss of that fineness of self-respect without which men and women are only so much clay—worthless dregs in the crucible of democracy.

Every tip given in the United States is a blow at our experiment in democracy. The custom announces to the world that at heart we are aristocratic, that we do not believe practically that "all men are created equal"; that the class distinctions forbidden by our organic law are instituted through social conventions and flourish in spite of our lofty professions.

Tipping’s problematic origins continue their legacy today in how tipping is essentially unfair. People are not tipped equally.

People of different races tip differently and are tipped differently, leading to discrimination both by workers (servers tend to provide worse service to Black and Hispanic customers because of a perceived propensity they will tip less) and by customers (see the disparity in received tips by race below).

Not only does race impact tipping, so do looks. Lookism is underrated as a societal problem, but it’s well documented that attractive people have it easier across the board and tips are no different.

A 2015 study found “Attractive servers earn roughly $1,261 more per year than unattractive servers.” Beauty has a larger impact on female than male server earnings, but beauty matters more for female than male customers. Interestingly, the difference in earnings is primarily driven by women tipping attractive women more.

Perhaps in a future post I can elaborate on how the gratuity system subsidizes corporate wages, or about wage theft, or about how tipping relates to class distinctions and dignity. Until then, I’ll leave the reader with the closing lines of William Scott’s The Itching Palm:

The campaign against tipping is much more than a purpose to save the money given in gratuities. Its idealism aims to reach the very pinnacle of republican society—the destiny toward which 1776 started us. The mountain peaks of pride will have to be pulled down and the valleys of false humility will have to be lifted up, while the impulses to greed and avarice will have to be rebuked until every American can say:

If I must build my pride upon another man's humility, I will not be proud; If I must build my strength upon another man's weakness, I will not be strong; If I must build my success upon another man's failure, I will not succeed!

… So anyway, if you liked this post, please feel free to leave me a tip! It’s not expected, just heavily encouraged!

Venmo: @michaelbatemanii

Bitcoin address: 3D4Td3sRknEdYEB4dxG31GnWg1u3TKFuLd

Ether address: 0x87DA854750B9A82F089d44D721aB08b9F9c0B878

Thanks to Irene and Shreyas. I’ll try to be funnier in the future.

"these POS vendors" 😂

Yeah, paying the slaves that prepare your food. What has the world come to.

(For all that don't get it: It's called sarcasm.)