Paradoxes, Principles, Permits

I think that public lands are so important for people to visit that we should limit how many people can visit them.

*note: things are not always going to be long. I just got carried away with this one.

I. Paradoxes

Anyone who enjoys the outdoors—hikers, climbers, skiers, fishermen, hunters, mountain bikers, surfers—also participates in an environmental paradox: these activities degrade the very resources upon which they depend. All outdoor activities require pristine natural environments as an integral component of the activity itself, but the activities lead to negative impacts like erosion, pollution, waste generation, and resource consumption. This resource paradox is made bitter by the fact that the people most worried about the environmental crisis contribute the most to the paradox.[1] To snowboard you need snow; to fish you need fish. Engaging in these activities, however, directly reduces our future capacity to enjoy them.

In 2018, I wrote dozens of pages on the environmental impact of mountaineering in my capstone thesis. During my research, I realized my mental model of how my activities impacted the world was myopic. Commentators and researchers used to contrast “appreciative” activities like biking and hiking with “consumptive” activities like fishing and hunting. The appreciate-consumptive labels, however, create a false distinction. Clearly, I reasoned, consumptive activities like hunting require careful resource management. Hunting involves the direct harvesting of limited numbers of animals, and unmanaged hunting leads to decimation (like the American buffalo) or annihilation (like the carrier pigeon) of species. Completing this research forced me to extend the logic to appreciative activities with concerning results.

All activities make us consumers of outdoor resources, whether it is the direct impacts of erosion we cause when we set up a campsite or the indirect effects of the emissions caused by flying thousands of miles for a skiing or climbing trip. In my thesis alone, which is far from a complete list and only focused on mountaineering and climbing, I discussed emissions from travel and production of equipment, waste generation, storage, and littering, various types of erosion and damage caused by gear, and increased infrastructure development in fragile and remote places. But as an illustrative case, I’d like to talk about waste—in particular, human waste.

One guy poops under a rock on a mountain while on a climbing trip—okay, no big deal. Multiply that action by hundreds, or thousands, or hundreds of thousands of people, however, and soon you won’t be able to find a rock to shit under. Unfortunately, that is exactly what has happened to mountains all over the world. Over the past 60 years, climbers have left 60-97 metric tons of shit along the most popular summit route for Denali in Alaska. Annually, climbers on that mountain produce an additional two metric tons of poop, most of which is dumped into glacial crevasses or simply left near campsites. Everest climbers leave behind more than 13 tons of human waste each year. Researchers on a climb of Aconcagua, the tallest mountain in South America, waxed poetic about the fecal conditions: “it is difficult to find rocks without fecal matter under them” and “used toilet paper flew through the camps and disappeared in the horizon.”

Unsurprisingly, tons of shit have shit-tons of impact. These shit tons of shit not only disrupt the subjective experience of being in an area, but they also impact water quality. Mountains supply 60%-80% of the world’s water, so spoiling the headwaters with human waste is definitely what I like to call a really bad move. This impact to water quality not only has (literal) downstream effects, but also makes it more likely that climbers will get sick. A detailed 2018 study of an Alaskan glacier found that poop particles can still pose a moderate risk to downstream water quality even decades after the initial contamination, although the risk is most acute for recreators on the glacier (the paradox strikes again).

Unfortunately, the practical context of activities like mountaineering means that, when in potentially life-threatening or physically demanding situations, a climber is always going to choose their own life over taking the time and effort to poop in a bag to “pack it out.” Likewise, the danger involved at alpine elevations makes cleanup expensive and dangerous, albeit still possible. This problem isn’t one that will just dissolve away either; due to elevation and cold temperatures, poop hangs around at elevation for decades, remaining toxic as mentioned above. Thus, the south side of Everest will probably remain, as eloquently described in Outside magazine, a “minefield of human excrement” for a long time.

Similar multiplicative impacts exist for trash waste, erosion, and irreparable damage to rock, biota, and biodiversity. While I originally looked at these impacts in the context of mountaineering, they’re applicable to basically all kinds of eco-tourism. Importantly, these are only direct impacts. Outdoor activities demand more infrastructure development like roads, lodging, restaurants, gas stations, bathrooms, and parking lots; new piers are constructed, climbing crags developed, and trails built. Additionally, travel, especially via airplane, has immense carbon impacts—an environmental sin I am especially guilty of.

As activities expand in scale and scope, impacts will scale with them; as pointed out by researcher Ralf Buckley, “In practice, the most fragile environments are wilderness areas with the least previous disturbance.” If more people are getting into the outdoors, then you would think that the tendrils of development would be expanding to accommodate them in relatively-unmarred areas. If impact scales with use, which I posit based on my research that it does, the empirical question becomes “Are outdoor activities expanding in popularity?”

II. Popularity

“Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.”

-Yogi Berra

The popularity of outdoor sports and tourism is climbing even faster than the CO2 concentration in the air. Just looking at the visitation numbers for U.S. national parks, you see traffic increase from hundreds of thousands of people at the start of the 20th century to hundreds of millions of visitors today.

After a lull in the 80s and 90s, Americans have rediscovered the allure of their public lands. Just in the last 15 years, visits have increased by 20% to almost 330 million people in 2019 (Sidenote: the decreases in 1990, 1995, 2013, and 2018 are presumably due to the government shutdowns which occurred in those years. There was also a large decrease in 2002 after 9/11). Then, the pandemic hit, doing things outside became one of the few acceptable forms of recreation, and this happened:

Last October, I was in Moab for a climbing trip. Driving back to my campsite, I saw a parking lot off the side of the road with cars parked end-to-end for a mile. I was confused, as this was just a random strip of highway in the desert. Quickly, I realized that it wasn’t a parking lot but the road pictured above: the entrance to Arches National Park, absolutely slammed with would-be visitors. Arches had closed its gates 80 times in 2021 as of June 21, 2021 due to crowding. The post-COVID National Parks rush is hitting parks everywhere; in May 2021, Yellowstone saw its busiest May of all time with more than 480,000 visitors. Grand Teton National Park also had a record month, with backcountry camping up 117% and trail use up 70% relative to 2019 levels. In short, more and more people are interested in our finite outdoor recreation resources.

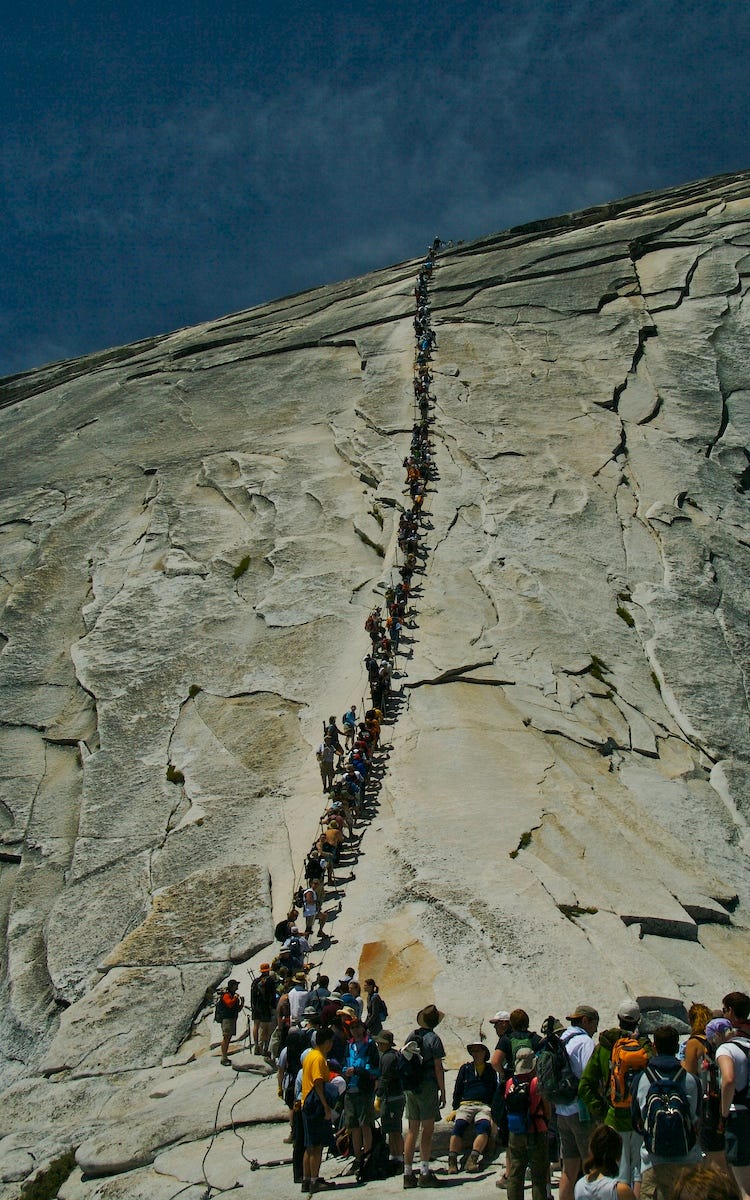

This phenomenon is not limited to the United States. Famous tourist and adventure destinations are starting to crack under the weight of their own popularity, in some cases literally; Machu Picchu in Peru, for instance, was almost placed on the UNESCO World Heritage in Danger list due to the impacts of erosion caused by the thousands of daily tourists and malignant behavior against the famous ruins. Famously, in 2019 the below photo was snapped on the summit ridge of Everest in a year when more than 800 people summited the mountain:

Not only is overcrowding harming these places and making them less enjoyable, but it is also in some cases increasing the danger level. A climber who was a part of the Everest traffic jam pictured above said that what should have taken 12 hours took 17 hours due to having to wait at bottlenecks. Overcrowding can increase the chance of rockfall, encountering severe weather, or simple exhaustion as detailed in this trip report of a climb on the Diamond on Long’s Peak. Although I can’t be sure about the experience levels of those involved (a friend pointed out that many of these deaths were from experienced skiers and boarders), the explosion of backcountry skiing’s popularity during COVID, coupled with a bad snowpack, contributed to the worst year of avalanche deaths since at least the 2009-2010 winter (as far back as this database goes) in the United States. Crowds cause damage to both people and places.

III. Principles

Despite what I may have written in my thesis about the promotion of Leave No Trace and community-based ethics, I now have zero faith in the general public to actually follow any set of principles that is the slightest inconvenience to what would be their default behavior. Call it a souring of collegiate idealism, but unless we better disincentivize collectively bad behavior, people will continue pursuing their own self-interest or whatever is easiest.

As a counterpoint to my own argument here, local systems of ethics in outdoor activities have proven to be powerful in establishing expectations and taboos on bad behavior. For example, local climbing ethics have been quite effective at establishing respect for first ascents and what kinds of routes are acceptable to bolt. With the exploding interest in the outdoors, however, I am not confident in the ability of communities to absorb the influx of new members to imbue new participants with the cultural taboos to prevent bad behavior fast enough. I predict the addition of climbing to the Olympics and the increase in the past few years of blockbuster climbing movies (Meru, Valley Uprising, Dawn Wall, Free Solo, the Alpinist, etc.) will only accelerate the growth in interest in our most fragile outdoor resources.

In the last sentence of my thesis, I wrote:

There is a path forward where climbers can continue to enjoy recreation in the mountains in a sustainable manner.

This take was optimistic but at the same time unambitious. The state of the natural world today demands not just sustainable action, but restorative. We need our actions to improve upon the status quo, not simply maintain it. Sustainability is just “a slower way to die”, whereas regeneration is a viable path toward the future.

If all outdoor activities are consumptive, and their popularity is skyrocketing, is it possible for these activities to be sustainable in the long term, much less restorative?

I’m not so sure. A recent NYT article, “Move Over, Sustainable Travel. Regenerative Travel Has Arrived”, made me more pessimistic than before I read it. This summary may be uncharitable, but the proposed “regenerative travel” seemed to be little more than tourists paying extra so that employees are paid better, local communities receive some investment, sometimes some carbon offsets are purchased, and tourism providers do a lot of impact accounting to track environmental and social impacts. All of these are objectively good things in my book, but they don’t do much to address any of the core problems of direct impact mentioned above except in one way: making things more expensive makes fewer people do them.

IV. Permits

The degradation of nature and the wild places we love is a tragedy of the commons issue. The commons represent our public lands, and overgrazing represents our ‘loving them to death.’ We already know how to solve the tragedy of the commons: close the commons. Traditionally, closing the commons has been taken as privatization. The last thing I would do is advocate for the privatization of our public lands; instead, I’d like to point to the original “Tragedy of the Commons” essay written by Garrett Hardin for a more palatable set of solutions. In fact, Hardin specifically wrote about national parks:

The National Parks present another instance of the working out of the tragedy of the commons. At present, they are open to all, without limit. The parks themselves are limited in extent--there is only one Yosemite Valley--whereas population seems to grow without limit. The values that visitors seek the parks are steadily eroded. Plainly, we must soon cease to treat the parks as commons or they will be of no value anyone.

What shall we do? We have several options. We might sell them off as private property. We might keep them as public property, but allocate the right enter them. The allocation might be on the basis of wealth, by the use of an auction system. It might be on the basis of merit, as defined by some agreed-upon standards. It might be by lottery. Or it might be on a first-come, first-served basis, administered to long queues. These, I think, are all reasonable possibilities. They are all objectionable. But we must choose--or acquiesce in the destruction of the commons that we call our National Parks.

For context, around 145 million people visited our National Parks in 1968, the year which this essay was written: less than half the number who visited last year.

Hardin suggests a way to determine the best method of closing the commons: mutually coercion, mutually agreed upon. He wrote:

To say that we mutually agree to coercion is not to say that we are required to enjoy it, or even to pretend we enjoy it. Who enjoys taxes? We all grumble about them. But we accept compulsory taxes because we recognize that voluntary taxes would favor the conscienceless. We institute and (grumblingly) support taxes and other coercive devices to escape the horror of the commons.

Just like taxes suck, any kind of permit system would suck. But the horror of the commons, I think, sucks more. Having to wait in lines in the middle of thousands of acres of wilderness sucks more. Trash littering the banks of rivers sucks more. Smog choking the lungs of humans and animals alike as it settles into mountain valleys sucks more. I think we’ve got to lean into permits and reservation systems.

Many of my friends know that I’m a big fan of markets and, more specifically, their ability to (dis)incentivize (bad) good behavior. When actions with bad externalities lack prices in a market, like emitting sulfur dioxide, bad things happen, like acid rain. History has shown that attaching prices to externalities, like the sulfur dioxide cap-and-trade program, is cost effective at reducing bad outcomes.

Making people pay for permits would reduce visitation, whether the permits were allocated via a flat fee open to everyone, an auction system, or through a lottery. Making things more expensive has a negative externality of its own, though: environmental equity. Gating people’s access to the outdoors with dollar sign-shaped fences would definitely decrease use, but at what cost?

There is an argument to be made that exposure to the outdoors is what makes us value things like our national parks in the first place, thus it seems wrong to put expensive permits in place to curtail use to less deleterious levels. Nepal’s working solution for its Everest permits is to charge foreigners, a group with relatively inelastic demand, $11,000 each to climb the mountain, but Nepali climbers only $750. Seniors in the U.S. already have access to discounted National Parks passes ($80 for a lifetime pass for those 62+ years old, versus $80 annual for everyone else). Tiered fee systems could be structured in various ways—by income, age, intended use—to not only minimize impact to equitable access but also to fund conservation and restoration efforts.

Another approach is to do away with fees altogether and create a lottery system to allocate permits. A number of parks in California have taken this approach, such as requiring permits to hike Yosemite’s Half Dome. This effort, however, may be having some bad consequences of its own: accidents on Half Dome have actually increased after implementing the permit system. Researchers hypothesize that the lucky winners of the lottery may feel more pressure to complete the hike because they feel like they won’t have the chance to do it again.

A final strategy could be the simple “first come, first serve” used by parks like Puerto Rico’s El Yunque National Forest. Either in person or online, the first person who grabs a permit is the lucky winner, and if they cancel a spot opens up for someone else.

The utility maximizer in me also doesn’t like these approaches as much because it doesn’t allow for allocation by utility; ideally, we’d design a system where people could express the value they place on getting a permit (e.g., by being willing to pay more for it). With that said, the ability to pay more for something sometimes just indicates relative wealth rather than utility, as dirtbaggers would be quick to point out. For what its worth, I don’t want national parks to become the playgrounds of the rich either. These kinds of systems (along with auctions or flat fees) also ignores merit; some of the best athletes in the world have been able to develop their craft via unfettered access to the unique outdoor resources on our public lands.

V. Passion

As oxymoronically noted by Hardin, all of these suggestions are reasonable, and they are all objectionable. But we need to implement something before we literally and figuratively erode the values away from the parks that give them their value in first place: biodiversity, natural beauty, connectedness to nature, and, perhaps most importantly to me personally, the feeling of the sublime.

I seek out outdoor experiences, in part, to experience the sublime. As defined by Edmund Burke:

The passion caused by the great and the sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is Astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror.

The subjective experience of looking out over the precipice of a rock face, with thousands of feet below you and a view of miles of rock, ice, and forest, with no clear human impact in sight, inspires a sense of smallness, insignificance, sometimes even terror, like the feeling of looking up at a bright sky and contemplating the implications of the milky way, or being on a boat so far out at see that you cannot see land, or turning off your headlamp deep in a cave; or being caught in a violent thunderstorm. The simplest way to turn the sublime into the mundane is to add a crowd, along with its associated noise, flashes of cameras, garbage and waste.

John Muir was kind of a crazy guy. A prodigious walker, Muir walked from Kentucky to Florida, purposefully choosing the most wild path possible, and from San Francisco to Yosemite, a walk that would change his life. Muir was so inspired by the Valley that he led the activism that turned Yosemite into the first national park. He camped with Teddy Roosevelt in Yosemite, convincing the President of the immense value of preserved land. Muir fought in vain against the damming of the Hetch Hetchy Valley within Yosemite.

My favorite story about Muir is described by the man himself in a chapter called “A Wind-storm in the Forests”. Facing an immense storm high in the mountains, Muir decides “it would be a fine thing to climb one of the trees to obtain a wider outlook and get my ear close to the Æolian music of its topmost needles.” He proceeds to climb a tree and sit in its top branches for hours, swinging as much as 30 degrees in the wind as he closed his eyes to listen:

The sounds of the storm corresponded gloriously with this wild exuberance of light and motion. The profound bass of the naked branches and boles booming like waterfalls; the quick, tense vibrations of the pine-needles, now rising to a shrill, whistling hiss, now falling to a silky murmur; the rustling of laurel groves in the dells, and the keen metallic click of leaf on leaf--all this was heard in easy analysis when the attention was calmly bent.

To me, this chapter embodies the sublime. The deep appreciation of the strength and power of nature, coupled with an intense awareness of the sights, smells, sounds, and sensations that go along with it, turned an alpine storm from a terrifying ordeal into a mystical, almost religious experience. I want the liberty to pursue this kind of Astonishment, but to maintain the character of the natural places that enables this feeling in the first place I am willing to give up some of that freedom.

Thanks to Jake Jose for the exchange of ideas.

[1] I am not implying that these activities are the greatest contributor to climate change as a whole, but rather that those who engage in these activities the most, and who presumably care the most about the planet, are the biggest contributor to the paradox.

I appreciate you taking the time to write this. I have honest questions:

1. Countless plants, insects, birds, and even mammals die and decompose in these areas. Why is human feces any worse? Not to mention how many insects, birds, mammals and other fauna excrete waste in the areas. Again, are humans not allowed to be part of the biome?

2. While I have no doubt that some national parks can become crowded, I find the argument that we are destroying these parks to be an emotional claim rather than an empirical claim. The fact that humans release feces is natural. Words like 'pristine' are used to tug at people's heartstrings, especially those who didn't grow up in wild and rural areas.

3. This reminds me of my daughter’s lament: "Dad, it's unfair! San Diego is so expensive, I can barely afford to live here!" Me: "Well, there are many amazingly beautiful places you can live that don't cost nearly as much. You get to make that choice. Make the sacrifice to live there or don't, it's up to you. Similarly, there are many, many parks to visit. If Yosemite or Mount Everest are too popular for your liking, there are many, many options besides those 2.

4. Again, thanks for the article. It was well written.

Michael, I was eating lunch! Great article, I think the solution is that everyone should hold in their poops 100% of the time. Become wholly efficient.