Kerouac the Cartographer

Time in the mountains compresses the topography of life into a day’s outing.

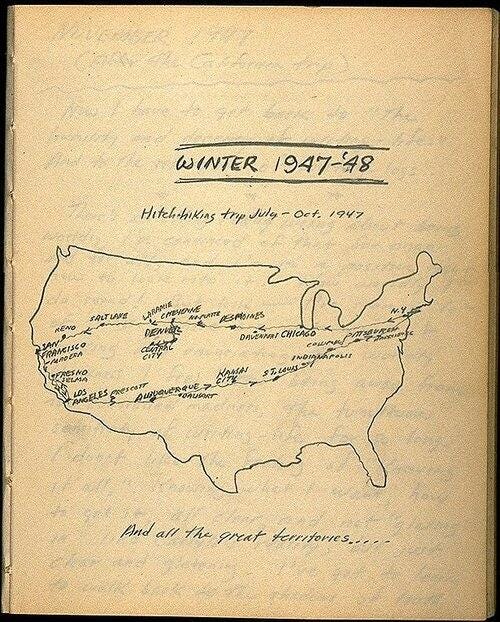

Jack Kerouac, the king of hipsterdom, popularizer of hitchhiking and Beat, the articulate drunk, was also a cartographer—his little-known specialty was topographic maps. Kerouac’s maps are drawn in his characteristic stream-of-consciousness deluges of words; the maps take the form of his novels. These maps trace the wild swings in elevation characteristic of the human experience. The juxtaposition of misery and triumph in the setting of a climb of California’s Matterhorn in The Dharma Bums brought this metaphorical curiosity to my attention. Kerouac wrote:

I nudged myself closer to the ledge and closed my eyes and thought 'Oh what a life this is, why do we have to be born in the first place, and only so we can have our poor gentle flesh laid out to such impossible horrors as huge mountains and rock and empty space,' and with horror I remembered the famous Zen saying, 'When you get to the top of a mountain, keep climbing.' The saying made my hair stand on end; it had been such cute poetry sitting on Alvah's straw mats. Now it was enough to make my heart pound and my heart bleed for being born at all.

Just a page later, however, after descending from near the summit he sang a different tune:

It was great. I took off my sneakers and poured out a couple of buckets of lava dust and said “Ah Japhy you taught me the final lesson of them all, you can’t fall off a mountain.

“And that’s what they mean by the saying, When you get to the top of a mountain keeping climbing, Smith.”

“Dammit that yodel of triumph of yours was the most beautiful thing I ever heard in my life. I wish I’d had a tape recorder to take it down.”

“Those things aren’t made to be heard by the people below,” says Japhy dead serious.

The wild oscillations from suffering to euphoria are, in my experience, one of the prime joys of the mountains. Reaching the limits of your endurance, thoughts of “what am I doing up here” or swears of “I’m never doing this again” are common. But always, when you finally reach the trailhead and everyone piles into the car to head home, a second wind inflates your sails with a mighty gust of excitement, achievement, and energy. On the drive back into town, plain sailing, you’re already planning next weekend’s trip. Growth occurs, both in terms of physical strength as well as, more importantly, mental fortitude. The blisters, the thirst, the fatigued muscles are what give the necessary contrast to the deliciously simple backcountry dinner that tastes better than a Michelin Star, the yells of victory after overcoming a hard pitch of climbing, and the exalted view from the peak’s summit.

Time spent in the mountains has the power to compress the topography of life into a day’s outing. It’s also about having a selective memory so that you’re willing to come back and do it again. Kerouac grasped this experiential juxtaposition well: again, in The Dharma Bums he wrote this apt simile:

Trails are like that: you you’re floating along in a Shakespearean Arden paradise and expect to see nymphs and fluteboys, then suddenly you’re struggling in a hot broiling sun of hell in dust and nettles and poison oak… just like life.

Life is like a trail: up and down, back and forth, pleasurable peaks and vexing valleys.

I think this simile also exists in the booze-fueled insanity of On the Road—although maybe instead of a trail it would be a mountain highway. Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty’s hedonistic quest to enjoy everything in search of “that last thing” takes them across North America in stolen and borrowed cars, driving for days on end or hitching for thousands of miles, sleeping on floors, in cheap motels, and on the ground, waking up after multi-day drinking binges in a miserable fog. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction; a big night of drinking and fighting in Central City, “great laughter rang from all sides,” “the girls were terrific,” turns into:

In the morning I woke up and turned over; a big cloud of dust rose from the mattress. I yanked at the window; it was nailed. Tim Gray was in the bed too. We coughed and sneezed. Our breakfast consisted of stale beer… Everything seemed to be collapsing… The sad ride back to Denver began.

Suddenly, we came down from the mountain and overlooked the great sea-plain of Denver; heat rose as from an oven. We began to sing songs. I was itching to get on to San Francisco.

Just like that: high, low, and back to high again! On the Road’s driving, drinking, drugging, degeneracy, in a strange way, essentialize the same undulations of experience as time in the mountains: high summits of ecstasy and nadiral ravines of suffering. “Just like life.”

Similarly, Big Sur captures the contour lines of the human experience in Duluouz’s trips to and from the cabin in the canyon. In the trips between San Francisco and Big Sur, Duluouz finds enlightenment and madness, clarity and paranoia, sobriety and overindulgence among the high seaside cliffs, the roaring waves of the Pacific, and the cabin’s solitude.

What can we learn from Kerouac and mountain climbing? Well, why do people climb mountains? Because they’re there, of course, is the best answer. But the instrumental value of mountain climbing is in how it makes the topography of subjective experience, that is really always there, stand out in a brilliant topo.

The act of climbing, then, is simply bringing a metaphor to life.

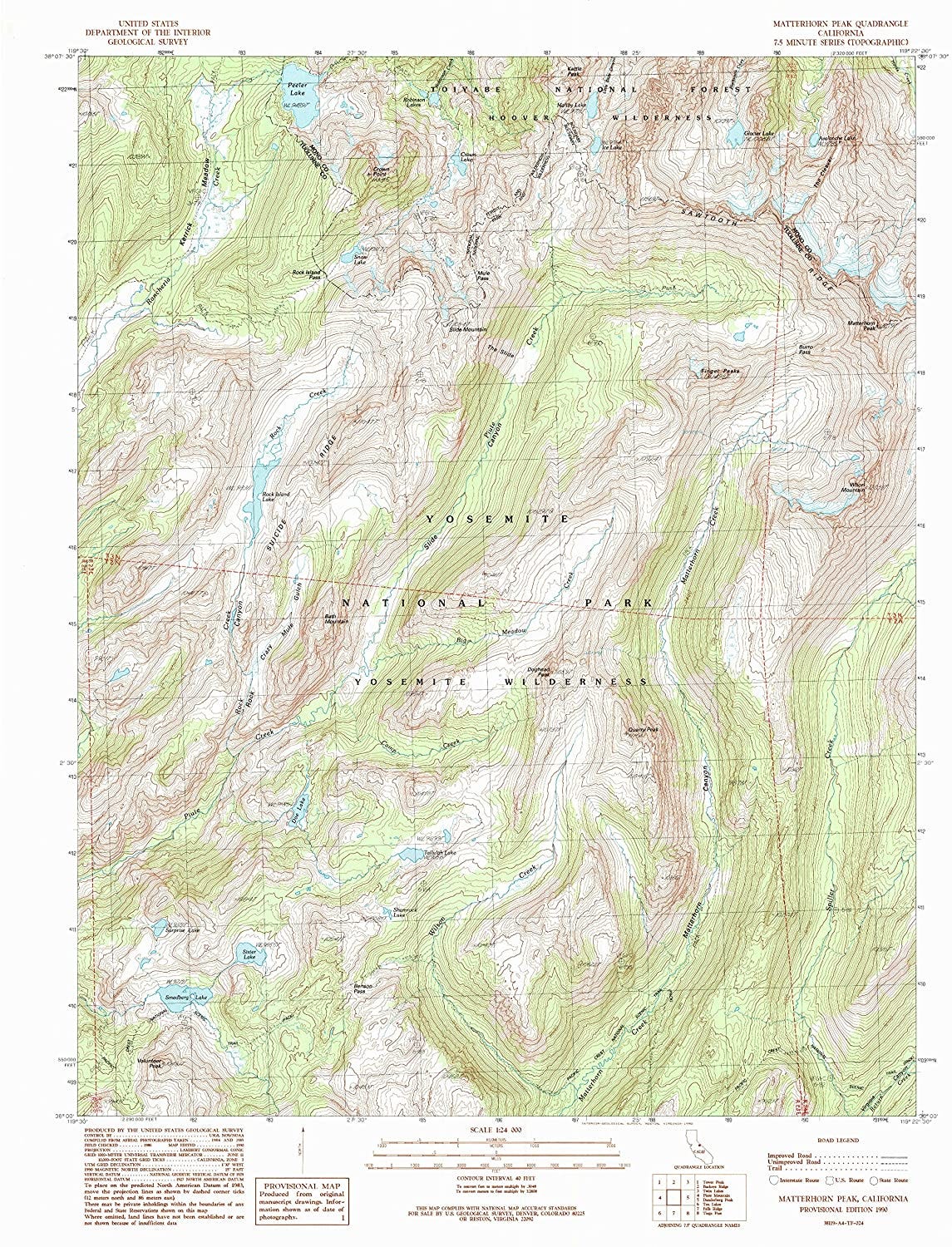

Actually examining the contour lines on a map as we navigate high passes and walk along rocky trails should make us realize a parallelism: our life is also a map; the highs and lows we experience when climbing a mountain are the same highs and lows we experience in our everyday life. “Comparisons are odious,” Japhy says, echoing Shakespeare after Kerouac’s character remarks how he’s glad to be in the mountains rather than drunk at his go-to bar, The Place, on a Saturday morning in the city. “It don’t make a damn frigging difference whether you’re in The Place or hiking up Matterhorn, its all the same old void, boy.”