It's All Relative

When something is described as normal, it begs the question: “relative to what?”

Apparently the average American planned on attending three concerts in 2023: most of my roommates went to all four nights of Labor Day Weekend Phish in Denver alone. My coworker just attended her 26th Dead and Company show on her 26th birthday, and continued attending their final five shows in Washington and California over the following two weeks. I’ve got a buddy who has to keep an Excel spreadsheet to keep track of his tickets and at least half a dozen friends with Gold Cash or Trade accounts (they pay a membership fee just for first dibs on face-value resale tickets to popular shows).

Most of my friends in Colorado ski at least 25 days a year. Many are much, much more obsessive than that: I know of at least three friends who skied more than 60 days this past year with full-time professional jobs, my new boss has skied the past 57 or so months in a row, and I have friends with more than five pairs of skis who think they need “just one more pair.” For perspective, only about 3% of Americans skied or boarded in 2021. Of those that skied, they averaged just 5.6 days spent on the mountain in a whole season.

Off the top of my head, I can think of at least a dozen close friends who run more than 30 miles a week. I have a few friends who win or podium in marathons and ultramarathons. I don’t need stats for this one—that’s obviously insane and beyond normal.

Even the fact that I’m writing this is abnormal: according to the 1% rule, 99% of participants in an internet community lurk, while only 1% create new content. Data suggests that this rule holds true across many large subreddits, Wikipedia edits, and Amazon reviews, just at a glance.

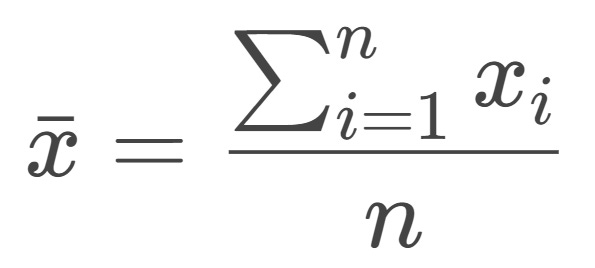

“Average” is a tough concept when it comes to those around us because of the immense effect of our social bubbles. “Average” is often conflated with “normal.” Whenever someone describes something as normal, though, it begs the question: “normal relative to what?”

It’s all relative—relative to what we do for work and for fun, who we spend time with, where we live, what we believe in. While there probably is something we could call an average American, or, more likely what we’re after, a modal American, whatever that person looks like likely isn’t a useful thing to know relative to our lived experience.

I’ve been using nationality as the level of analysis here. That decision was arbitrary. I could be talking of Coloradans or citizens of Earth, or use other categories like common hobby (“climbers”), religious belief (“Muslims”), or political ideology (“Democratic Socialists”). Social selection effects ensure that what my “normal” is will be “abnormal” in some way.

When the perceived extremes of my peers overwhelm me, I try and remember: comparisons are odious. I also imagine that I contribute to others’ sense of extremity just as much as they contribute to mine. The variety of experience of my friends and colleagues is amazing and worth celebrating. Who cares what is normal, relative to however you define it.