You shall not go down twice to the same river, nor can you go home again. That he knew; indeed it was the basis of his view of the world. Yet from that acceptance of transience he evolved his vast theory, wherein what is most changeable is shown to be fullest of eternity, and your relationship to the river, and the river's relationship to you and to itself, turns out to be at once more complex and more reassuring than a mere lack of identity. You can go home again… so long as you understand that home is a place where you have never been.

—Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia

You stand beside a stream. A gentle breeze parts the fronds of ferns growing along the shoreline next to you. Clear, cold water bubbles over a stack of boulders stretching to the opposite shore and swirls into an eddy after the rapids. An iridescent sheen hugs the surface of the water, its rainbow geometries reflecting the dazzling evening sunlight.

A heavy cloud slides over the sun, darkening the sky as you crouch by the stream and dip your finger into the eddy. The lustrous layer elongates, then quickly reforms as you remove your finger to smell it. Oil. You close your eyes.

The stream flows backwards.

The sheen swirls to the edge of the eddy and the main flow of the river slowly absorbs the layer of oil. It flows upstream with the reversed water, cascading up the line of boulders and against the gradient of the river. At a fork, the swirling sheen retreats up a smaller tributary into a mountain canyon.

Granite faces watch with somber eyes of lichen as the oil continues its climb toward the nearby mountain pass. A narrow strip of road runs parallel to the stream. At a rough pullout, a car sits, parked.

The sheen concentrates at the shoreline and forms a thin river of its own up the contours of the bank, through the stubby grass, and into the dirt of the pullout. The withdrawing stream of oil oozes its way through the rocks and dirt until it congeals into a large puddle below the car. A steady drip of oil flows up into the car’s cracked oil pan, shrinking the puddle until the dirt is again dry beneath the shadow of the car. The owners of the vehicle return and start the ignition. The car reverses out of the lot, bottoming out as it returns to the road, uncracking the oil pan.

The oil circulates through the engine, lubricating the pistons and endlessly circulating through gaskets, filters, and hoses. The car turns off and on and off again in cycles of action and idleness. Heat and coolness. Cacophony and silence.

As the oil circulates and cycles, it becomes less sludgy. Cleaner. Smoother. Eventually, at a garage, a technician removes the oil cap and the reservoir of oil begins to flow up again, out of the car, through a funnel, and back into a five-quart plastic jug of motor oil.

The jug is placed back on the shelf of the garage, where it patiently sits until another worker arrives in a truck, stacks the jug onto a pallet full of other motor oil jugs and windshield wiper fluid, and drives the pallet back to a distribution center.

More trucks and more logistics return the jug to a refinery, where the oil pours out of the jug and into a vast holding tank. Here, the cocktail of additives and dispersants separate themselves from the oil, and the refinery vaporizes and condenses the oil over and over again, running it through miles of pipes, tanks, and towers until a yellow-black liquid hydrocarbon enters a larger pipeline and exits the refinery.

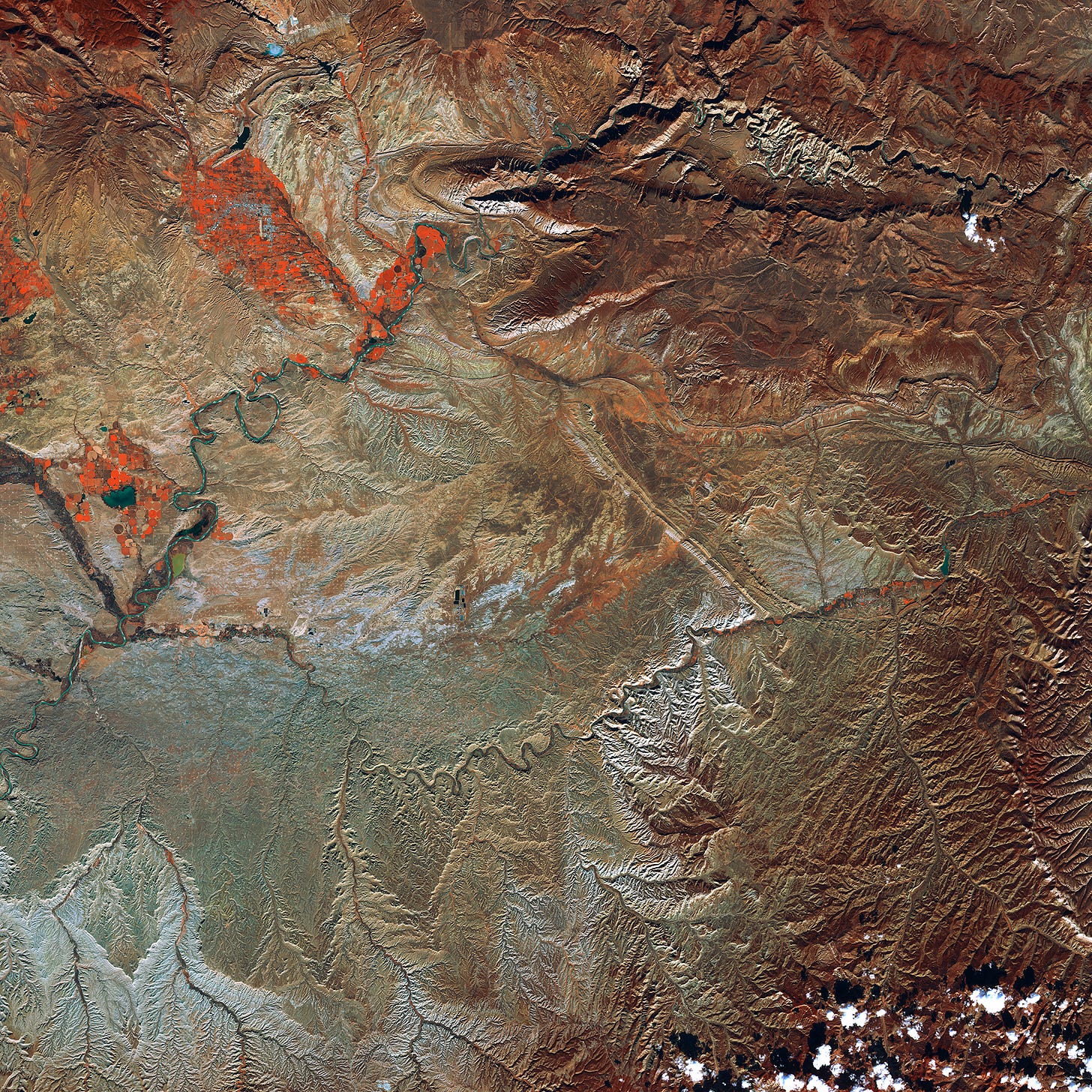

Pipelines and tanker trucks bring the crude oil back to a rig in the badlands of Utah, where a pumpjack pushes the oil a thousand feet below the surface. There, it percolates into the porous sands and joins a reservoir.

For fifty million years, the heat and pressure of the Earth slowly recede against the reservoir; the oil reverts to kerogen, and the kerogen to a mixture of organic matter. Layers of sediment uncover the reservoir until the deep waters of an ancient ocean touch the organic matter: algae. The dead algal bloom alights from the floor of the sea, turning from black, to brown, to chlorophyllic green as the plant rises to the surface, alive once again. Soft waves lap at the floating algae as the sun blazes down from above.

The algae sucks in oxygen and emits carbon dioxide, water, and energy as light. A photon of light beams its way skyward, blasting through the atmosphere and, for 498 seconds, it shoots through the cosmos. One second later, it reenters the exploding corona of the Sun.

The photon bounces around the interior layers of the sun for 200,000 years before rushing toward a helium atom near its core. A massive implosion of energy separates the helium into hydrogen atoms. For four and a half billion years, the hydrogen sits in the core of the Sun, compressed into a dense ball of plasma until the Sun’s gravity unwinds the core into a spinning nebula of gas and dust.

The hydrogen atom floats through the Universe for nearly ten billion years. For this duration, the matter leaves and joins stars, solar systems, and galaxies; it recombinates and reionizes.

All of the matter of the Universe draws together. Molecules become atoms; atoms become subatomic particles.

The Universe collapses. Fundamental physical forces and the laws of physics cease to exist.

All matter fuses into one point of infinite density and temperature.

One single point in the darkness.

Darkness.

…

A point of light appears.

The point glows brighter. Orange and gold nebulae grow to cover your entire field of view.

Warmth touches your skin. You open your eyes, squinting; the sky has parted, revealing the evening sun ablaze with calm glory.

Rays of light pierce the leaves of the trees hugging the shore, casting mottled green shadows over the smooth boulders strewn across the river. A cicada plays its evening song over the gurgle of the tumbling water. The watercolor sky, awash in pinks and yellows, silhouettes the crests of mountains on the horizon.

In the distance, you hear the choke and sputter of a car’s engine coming to life. You close your eyes again.

Thanks to Jake for prompts to take things further, Ian for, as always, technical correctness w/r/t hydrology and snow science, and Frank for the stoke.